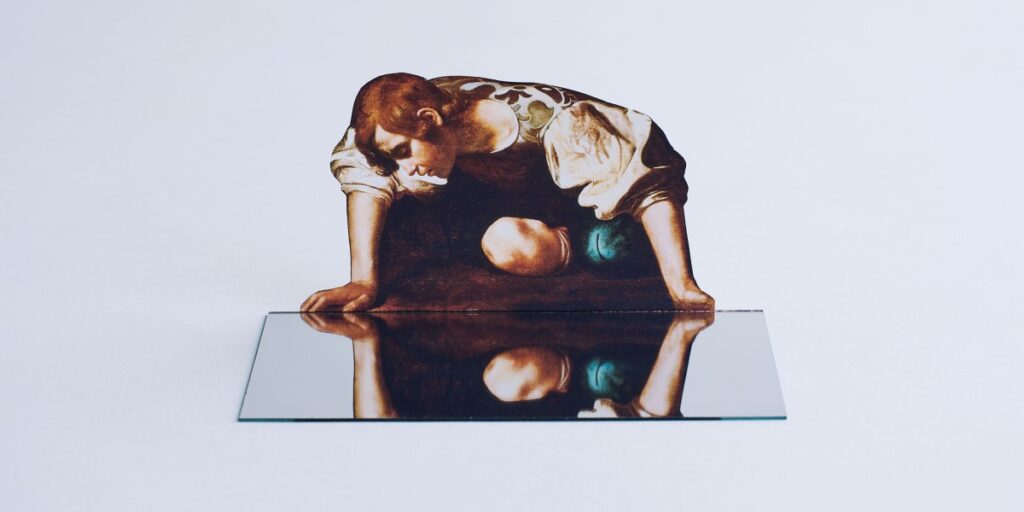

A certain level of disillusionment was bound to occur. The introduction of OpenAI’s free web app, ChatGPT, in late 2022, significantly altered the trajectory of an entire industry and several global economies. Many individuals began interacting with their computers, and these machines responded, leading to heightened expectations.

In response, technology companies rapidly developed competing products, each new release surpassing the last with capabilities in voice, images, and video. Through continuous innovation, AI firms consistently presented new products as significant breakthroughs, fostering a belief that the technology would only improve. Proponents suggested exponential progress, often sharing charts to illustrate rapid advancements. Generative AI appeared to possess limitless potential.

However, 2025 has emerged as a period of reassessment for the AI industry.

Initially, leaders of prominent AI companies made ambitious promises that proved difficult to fulfill. Claims included that generative AI would displace white-collar workers, usher in an era of abundance, facilitate scientific breakthroughs, and aid in discovering new disease cures. This created a sense of urgency across global economies, particularly in the Global North, prompting CEOs to re-evaluate strategies and invest in AI initiatives.

The initial enthusiasm began to wane. Despite being promoted as a versatile tool capable of modernizing business operations and reducing expenses, several studies this year indicate that companies are struggling to implement AI effectively. Data from various sources, including the US Census Bureau and Stanford University, reveal a stagnation in business adoption of AI tools. Furthermore, many pilot projects often remain in the experimental phase. Without widespread economic integration, it is uncertain how major AI companies will recover the substantial investments made in this competitive landscape.

Concurrently, advancements in the core AI technology no longer represent the significant leaps seen previously.

A notable instance of this trend was the less-than-stellar launch of GPT-5 in August. OpenAI, a company largely responsible for initiating and sustaining the current AI boom, was poised to unveil a new generation of its technology. For months, OpenAI had promoted GPT-5, with CEO Sam Altman proclaiming it a “PhD-level expert in anything.” Altman also shared an image of the Death Star from Star Wars, which followers interpreted as a symbol of immense power, fueling massive expectations.

However, upon its release, GPT-5 appeared to offer incremental improvements rather than revolutionary changes. This led to a significant shift in perception, reminiscent of the initial launch of ChatGPT three years prior. Yannic Kilcher, an AI researcher and prominent YouTuber,

stated two days after GPT-5’s release that “The era of boundary-breaking advancements is over,” adding, “AGI is not coming. It seems very much that we’re in the Samsung Galaxy era of LLMs.”

Many have drawn parallels between the current state of AI and the evolution of smartphones. For about a decade, smartphones represented the pinnacle of consumer technology excitement. Now, new releases from companies like Apple or Samsung often occur with minimal public enthusiasm. While dedicated enthusiasts analyze minor enhancements, for most users, a new iPhone largely resembles its predecessor. This raises the question of whether generative AI is entering a similar phase. If so, is it a concern? Smartphones, despite their incremental updates, have become ubiquitous and fundamentally transformed global operations.

It is important to acknowledge that recent years have indeed featured impressive advancements, including significant improvements in video generation models, the problem-solving capabilities of reasoning models, and the top-tier performance of the newest coding and math models in competitions. However, this remarkable technology is still relatively new and largely experimental. Its achievements are often accompanied by significant limitations.

A recalibration of expectations may be necessary.

The big reset

Caution is advised, as the shift from excessive hype to skepticism can be extreme. Dismissing this technology solely because it has been over-marketed would be premature. The immediate reaction to AI not meeting its hype often suggests that progress has stalled. However, this perspective overlooks the nature of research and innovation in technology, where progress typically occurs in irregular bursts, with challenges often overcome through various approaches.

Considering the GPT-5 launch in context, it followed closely after OpenAI’s release of several impressive models in prior months. These included o1 and o3, groundbreaking reasoning models that presented a new industry paradigm, and Sora 2, which again elevated standards for video generation. This sequence of developments does not suggest a halt in progress.

AI capabilities remain impressive. For instance, Google DeepMind’s new image generation model, Nano Banana Pro, can transform a book chapter into an infographic and offers many other features, available freely on smartphones.

Nevertheless, questions arise: What remains once the initial ‘wow’ factor dissipates? How will this technology be perceived in one or five years? Will its significant financial and environmental costs be deemed justifiable?

Considering these points, here are four perspectives on the state of AI at the close of 2025, marking the beginning of a necessary adjustment in expectations.

01: LLMs are not everything

In certain respects, the overemphasis on large language models (LLMs), rather than AI in its entirety, requires adjustment. It has become clear that LLMs do not represent the path to artificial general intelligence (AGI), a theoretical technology some believe will eventually perform any cognitive task a human can.

Even Ilya Sutskever, a proponent of AGI and cofounder of Safe Superintelligence (and formerly OpenAI’s chief scientist), now points out the limitations of LLMs, a technology he significantly contributed to creating. While LLMs excel at learning numerous specific tasks, they do not appear to grasp the underlying principles, as Sutskever noted in an

in November.

This distinction is akin to learning to solve a thousand specific algebra problems versus understanding how to solve any algebra problem. Sutskever emphasized that “The thing which is most fundamental is that these models somehow just generalize dramatically worse than people.”

The compelling linguistic abilities of LLMs make it easy to assume they can perform any task. The technology’s capacity to emulate human writing and speech is remarkable. Humans are inherently inclined to perceive intelligence in behaviors that resemble their own, regardless of whether true intelligence is present. Consequently, machines exhibiting humanlike behavior often lead observers to attribute a humanlike mind to them.

This phenomenon is understandable, given that LLMs have only recently entered mainstream awareness. During this period, marketing efforts have capitalized on a limited public understanding of the technology’s true capabilities, inflating expectations and accelerating hype. As familiarity with this technology grows, a more realistic understanding of its potential should emerge.

02: AI is not a quick fix to all your problems

In July, MIT researchers released a study that became a central argument for those expressing disillusionment. The primary finding indicated that a substantial 95% of businesses attempting to use AI reported no discernible value.

This assertion was corroborated by additional research. A November study from Upwork, an online freelancing platform, revealed that agents utilizing leading LLMs from OpenAI, Google DeepMind, and Anthropic were unable to independently complete many common workplace tasks.

This outcome significantly deviates from Sam Altman’s January prediction, where he wrote on his personal blog, “In 2025, the first AI agents may join the workforce and substantially alter company output.”

However, a crucial detail often overlooked in the MIT study is the narrow definition of success used by the researchers. The 95% failure rate applied to companies that had attempted to implement custom AI systems but had not scaled them beyond the pilot phase within six months. It is not unexpected for many experiments with new technology to require time before yielding widespread success.

Furthermore, this figure did not encompass the use of LLMs by employees operating outside official pilot programs. The MIT researchers observed that approximately 90% of surveyed companies exhibited an “AI shadow economy,” where workers independently utilized personal chatbot accounts. The economic impact of this shadow economy, however, was not quantified.

When the Upwork study examined task completion rates for AI agents collaborating with knowledgeable human users, success rates significantly increased. This suggests that many individuals are independently discovering how AI can assist them in their professional roles.

This observation aligns with Andrej Karpathy’s insight: Chatbots often surpass the average human in various tasks (such as legal advice, bug fixing, or high school math), but they do not outperform human experts. Karpathy posits that this explains why chatbots have gained popularity among individual consumers, assisting non-experts with daily tasks, yet have not revolutionized the economy, which would necessitate exceeding the performance of skilled professionals.

This situation may evolve. Currently, it is not surprising that AI has not (yet) delivered the job market impact predicted by its proponents. AI is not a simple solution and cannot replace human workers. However, significant potential remains, and the methods for integrating AI into daily workflows and business processes are still under exploration.

03: Are we in a bubble? (If so, what kind of bubble?)

If AI constitutes a market bubble, its nature prompts comparison to the subprime mortgage crisis of 2008 or the internet bubble of 2000, noting significant distinctions between them.

The subprime bubble devastated a substantial portion of the economy, leaving behind only debt and inflated real estate values upon its collapse. In contrast, the dot-com bubble, while eliminating many companies and causing global repercussions, ultimately left behind the nascent internet—an international network and a few startups, such as Google and Amazon, which evolved into today’s tech giants.

Alternatively, the current situation might represent a unique type of bubble. Presently, a definitive business model for LLMs is lacking. The ‘killer app’ for this technology, or even if one will emerge, remains unknown.

Economists express concern over the unprecedented capital invested in infrastructure to meet projected demand. A key question is whether this demand will actually materialize. The unusual circularity of many deals—such as Nvidia funding OpenAI, which then funds Nvidia—further contributes to varied predictions about future outcomes.

Some investors maintain an optimistic outlook. During an

on the Technology Business Programming Network podcast in November, Glenn Hutchins, cofounder of Silver Lake Partners, an international private equity firm, offered reasons for reassurance. He stated that “Every one of these data centers—almost all of them—has a solvent counterparty that is contracted to take all the output they’re built to suit.” This implies that demand is pre-secured, rather than relying on future interest.

Hutchins also highlighted Microsoft as one of the largest solvent counterparties. He noted, “Microsoft has the world’s best credit rating. If a deal is signed with Microsoft to take the output from a data center, Satya (Nadella) guarantees it.”

Many CEOs are likely reflecting on the dot-com bubble to extract lessons. One interpretation is that companies that failed then lacked the financial resources to endure. Those that survived the downturn subsequently prospered.

Applying this lesson, contemporary AI companies are endeavoring to finance their operations through what might be a market bubble. The imperative is to remain competitive and avoid falling behind, though this strategy represents a significant risk.

However, another lesson exists: companies initially perceived as niche can rapidly achieve significant valuations. For example, Synthesia, a provider of avatar generation tools for businesses, was initially met with skepticism. Nathan Benaich, cofounder of Air Street Capital, recalls his uncertainty about the technology’s purpose and market viability a few years ago, amidst widespread concerns about deepfakes.

Benaich stated, “It was unclear who would pay for lip-synching and voice cloning. It turns out many people were willing to pay for it.” Synthesia currently serves approximately 55,000 corporate clients, generating around $150 million annually, and was valued at $4 billion in October.

04: ChatGPT was not the beginning, and it won’t be the end

ChatGPT represented the culmination of a decade of advancements in deep learning, the foundational technology for contemporary AI. Deep learning’s origins trace back to the 1980s, and the broader field of AI dates to at least the 1950s. Viewed within this historical context, generative AI is still in its early stages.

Concurrently, research activity is intense. Major AI conferences worldwide are receiving an unprecedented number of high-quality submissions. This year, some conference organizers even declined papers that had already received reviewer approval, simply due to volume. Simultaneously, preprint servers such as arXiv have experienced an influx of AI-generated research content.

Sutskever, in the Dwarkesh interview, described the current limitations with LLMs as a return to “the age of research.” This is presented not as a setback, but as the beginning of a new phase.

Benaich acknowledges the presence of “hype beasts” but sees a positive aspect: hype draws in the necessary funding and talent for genuine progress. He noted that “only two or three years ago, the individuals who built these models were essentially research nerds who stumbled upon something that somewhat functioned. Now, everyone proficient in technology is engaged in this field.”

Where do we go from here?

The persistent hype surrounding AI originates not solely from companies promoting their costly new technologies. A significant number of individuals, both within and outside the industry, are eager to believe in the potential of machines that can read, write, and think. This represents a long-standing, ambitious dream.

However, such hype was never sustainable, which is a positive development. There is now an opportunity to adjust expectations and perceive this technology for its actual nature—to evaluate its true capabilities, comprehend its limitations, and dedicate time to learning how to apply it in meaningful and advantageous ways. Benaich commented, “Researchers are still trying to figure out how to invoke certain behaviors from this insanely high-dimensional black box of information and skills.”

This adjustment in AI expectations was long overdue. Nevertheless, AI is not disappearing. The full scope of what has been developed so far, let alone future advancements, is not yet completely understood.