The Firefox crash reporter is a critical component, though ideally, users rarely encounter it. It provides crucial insights into the most severe bugs: those that cause the main browser process to crash. Such crashes result in the worst user experience, as the entire application closes, making their resolution a top priority. While other crash types, like tab crashes, can often be managed and reported by the browser without user intervention, a main process halt necessitates a distinct application to collect crash data and communicate with the user.

This article outlines the strategy employed to rewrite the crash reporter using Rust. It explores the rationale for this rewrite, the unique characteristics of the crash reporter application, the architectural design implemented, and specific implementation details.

Why Rewrite?

Despite the importance of managing main process crashes effectively, the crash reporter had not seen substantial development recently, beyond ensuring reliable crash report and telemetry delivery. It had reached a point of being “good enough” but challenging to maintain. The existing system included three separate GUI implementations (for Windows, GTK+ for Linux, and macOS), abstraction layers primarily in C++ and Objective-C for macOS, a binary component from outdated Apple development tools, and lacked a test suite. Consequently, a backlog of unaddressed features and improvements had accumulated.

Recent efforts have successfully reduced crash rates, through both significant advancements and numerous minor bug fixes. During this period, the crash reporter performed adequately. However, a critical juncture has been reached where enhancing the crash reporter could yield valuable data to further reduce crash rates. Given the difficulties and potential for errors in improving the existing codebase, a decision was made to rewrite the application. This approach aims to facilitate easier implementation of pending features and enhance the quality of crash reports.

Consistent with other Firefox components, Rust was chosen for this rewrite to create a more reliable and maintainable program. Beyond Rust’s well-known memory safety features, its type system and standard library significantly enhance code reasoning, error handling, and the development of robust, comprehensive cross-platform applications.

Crash Reporting is an Edge Case

The crash reporter possesses several unique characteristics, particularly when compared to other components migrated to Rust. Notably, it operates as a standalone application, a distinction from most other Firefox components. While Firefox employs multiple processes for sandboxing and crash isolation, these processes typically communicate and share a common codebase.

A critical requirement for the crash reporter is to minimize its reliance on the Firefox codebase, ideally using none at all. This prevents the reporter from depending on potentially buggy code that could cause it to crash. An entirely independent implementation ensures that a main process crash will not compromise the reporter’s functionality.

The crash reporter also requires a graphical user interface (GUI). While this isn’t unique among Firefox components, it cannot utilize Firefox’s built-in cross-platform rendering capabilities. Therefore, a separate, independent cross-platform GUI implementation was necessary. Although using an existing cross-platform GUI crate might seem logical, several factors advised against it.

- Minimizing external code was a priority to enhance crash reporter reliability, aiming for the simplest and most auditable design possible.

- Firefox incorporates all dependencies directly within its codebase, making the inclusion of potentially large GUI libraries undesirable.

- Few third-party crates offer a native operating system look and feel or directly utilize native GUI APIs. A native appearance is preferred for the crash reporter to ensure user familiarity and leverage accessibility features.

Consequently, third-party cross-platform GUI libraries were not considered a suitable option.

These specific requirements significantly constrained the viable development approaches.

Building a GUI View Abstraction

To enhance the crash reporter’s maintainability and facilitate future feature additions, the goal was to minimize platform-specific code. This was achieved by employing a simple UI model, which could then be translated into native GUI code for each target platform. Each UI implementation is required to provide two methods (operating on arbitrary platform-specific &self data):

/// Run a UI loop, displaying all windows of the application until it terminates.

fn run_loop(&self, app: model::Application)

/// Invoke a function asynchronously on the UI loop thread.

fn invoke(&self, f: model::InvokeFn)

The run_loop function is straightforward: the UI implementation accepts an Application model (to be detailed later) and executes the application, blocking until its completion. The target platforms generally share similar threading assumptions, where the UI operates on a single thread, typically running an event loop that blocks on new events until an application-ending event is received.

In certain scenarios, asynchronous function execution on the UI thread is necessary (e.g., displaying a window, updating a text field). As run_loop is blocking, the invoke method defines this asynchronous capability. This threading model simplifies the use of platform GUI frameworks, ensuring all native function calls occur on a single thread (the main thread) throughout the program’s execution.

It is appropriate to detail the structure of each UI implementation. Challenges for each will be discussed subsequently. Four UI implementations exist:

- A Windows implementation leveraging the Win32 API.

- A macOS implementation built with Cocoa (AppKit and Foundation frameworks).

- A Linux implementation utilizing GTK+ 3 (referred to as “GTK” as the “+” has been dropped in GTK 4). Linux lacks native GUI primitives, and since GTK is already bundled with Firefox on Linux for a modern GUI, it was also adopted for the crash reporter. Platforms not directly supported, such as BSDs, also employ the GTK implementation.

- A testing implementation designed to allow tests to interact with a virtual UI, simulating interactions and reading state.

A final point before proceeding: the current crash reporter features a relatively simple GUI. Therefore, a deliberate non-goal of the development was to create a standalone Rust GUI crate. The aim was to develop only the necessary abstraction to meet the crash reporter’s specific requirements. While additional controls can be incorporated into the abstraction if needed in the future, efforts were focused on avoiding unnecessary development to cover all possible GUI use cases.

Similarly, efforts were made to prevent superfluous development by accepting some degree of workarounds and inherent edge cases. For instance, the model defines a Button as an element capable of containing any arbitrary element. However, implementing this fully with Win32 or AppKit would have demanded extensive custom code. Consequently, a specific case was made for a Button containing a Label, which suffices for current needs and is a readily available primitive. Such special cases are minimal, but their inclusion was deemed acceptable where necessary.

The UI Model

The UI model is a declarative structure primarily based on GTK concepts. GTK’s maturity and established high-level UI concepts made it suitable for the abstraction, simplifying the GTK implementation. For example, GTK’s straightforward layout method, which uses container GUI elements and per-element margins/alignments, was sufficient for the GUI, leading to similar definitions in the model. This “simple” layout definition is, however, somewhat high-level, adding complexity to the macOS and Windows implementations, though this trade-off was considered worthwhile for the ease of UI model creation.

The top-level type of the UI model is Application. This is relatively simple: an Application is defined as a collection of top-level Windows (though the current application uses only one) and an indicator of whether the current locale is right-to-left. Firefox resources are examined to ensure the same locale is used as Firefox, avoiding reliance on the native GUI’s locale settings.

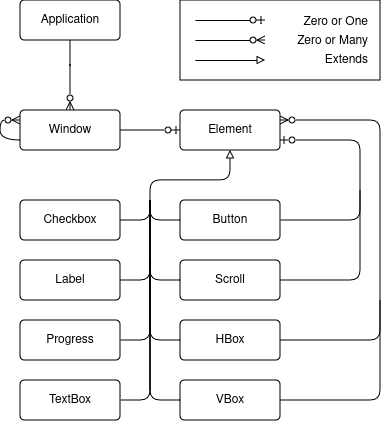

As anticipated, each Window encapsulates a single root element. The remainder of the model comprises a few common container and primitive GUI elements:

The crash reporter requires only eight types of GUI elements. The Progress element currently functions as a spinner rather than indicating actual progress, making it not strictly essential but a useful visual.

Rust does not natively support object-oriented inheritance, which might raise questions about how each GUI element “extends” Element. The depicted relationship is conceptual; the implemented Element structure is as follows:

pub struct Element {

pub style: ElementStyle,

pub element_type: ElementType

}

Here, ElementStyle encompasses all common element properties (alignment, size, margin, visibility, and enabled state), while ElementType is an enum with each specific GUI element as a variant.

Building the Model

Model elements are designed for consumption by UI implementations, hence most fields have public visibility. To provide a distinct interface for constructing elements, an ElementBuilder<T> type was defined. This type includes methods that enforce assertions and offer convenient setters. For example, many methods accept parameters that implement Into<MemberType>, and some methods, like margin(), set multiple values (though more specific options like margin_top() are available).

A general impl<T> ElementBuilder<T> exists, providing setters for various ElementStyle properties. Additionally, each specific element type can offer its own impl ElementBuilder<SpecificElement> with properties unique to that element type.

The ElementBuilder<T> is combined with a ui! macro, which enables declarative UI definition. For instance, it allows the following syntax:

let details_window = ui! {

Window title("Crash Details") visible(show_details) modal(true) hsize(600) vsize(400)

halign(Alignment::Fill) valign(Alignment::Fill)

{

VBox margin(10) spacing(10) halign(Alignment::Fill) valign(Alignment::Fill) {

Scroll halign(Alignment::Fill) valign(Alignment::Fill) {

TextBox content(details) halign(Alignment::Fill) valign(Alignment::Fill)

},

Button halign(Alignment::End) on_click(move || *show_details.borrow_mut() = false)

{

Label text("Ok")

}

}

}

};

The ui! macro’s implementation is relatively simple. The initial identifier specifies the element type, and an ElementBuilder<T> is instantiated. Subsequently, the remaining method-call-like syntax forms are invoked on the mutable builder.

Optionally, curly braces denote that an element has children. In such cases, the macro is recursively invoked to create these children, and add_child is called on the builder with the result (requiring the builder to possess an add_child method). While the syntax transformation is straightforward, this macro offers more than mere syntactic sugar; it significantly enhances UI readability and editing by representing the element hierarchy directly in the syntax. A drawback, however, is the lack of automatic formatting support for such macro DSLs, necessitating manual formatting maintenance by developers.

With the model defined and a declarative method for its construction, dynamic runtime behaviors remain to be addressed. The preceding example illustrates an on_click handler being set on a Button, and the Window‘s visible property being linked to a show_details value that changes upon on_click. This declarative UI is integrated with simple data binding primitives, allowing UI implementations to interact with and react to runtime events.

Many modern GUI frameworks, across various languages including Rust, employ a “diffing element trees” architecture (similar to React). In this paradigm, code is largely functional and side-effect-free, generating the GUI view as a function of the current state. This approach offers benefits, such as simplifying the creation, comprehension, and maintenance of complex, stateful layout changes, and promoting a clear separation between model and view. However, since a full framework was not being developed, and the application is expected to remain relatively simple, the advantages of such an architecture did not outweigh the increased development effort. The implemented approach more closely resembles the MVVM architecture:

- the model refers to the structure discussed previously;

- the views are the distinct UI implementations; and

- the viewmodel, broadly speaking, encompasses the data bindings.

Data Binding

Several types are utilized to declare dynamic, runtime-changeable values. The UI required support for distinct behaviors:

- triggering events, such as actions upon a button click,

- synchronized values that reflect and broadcast changes to all copies, and

- on-demand values that can be queried for their current state.

On-demand values retrieve textbox contents instead of synchronized values, a choice made to circumvent the need for implementing debouncing in each UI. While not excessively complex to implement, supporting the on-demand approach was also straightforward.

For convenience, a Property type was developed to encapsulate value-oriented fields. A Property<T> can be assigned a static value (T), a synchronized value (Synchronized<T>), or an on-demand value (OnDemand<T>). It supports impl From for each of these, enabling builder methods to accept fn my_method(&mut self, value: impl Into<Property<T>>) and allowing any supported value to be passed in a UI declaration.

The implementation will not be discussed in detail (it aligns with expectations), but it is notable that these types are all Clone for easy sharing of data bindings. They utilize Rc (as thread safety is not required) and RefCell where necessary to access callbacks.

In the previous example, show_details is a Synchronized<bool> value. When this value changes, the UI implementations adjust the associated window’s visibility. The Button‘s on_click callback sets the synchronized value to false, thereby hiding the window (the details window in this example is never closed, only shown and hidden).

Previously, data binding types included a lifetime parameter to define the validity duration of event callbacks. Although functional, this approach significantly complicated the code, particularly due to the inability to convey correct lifetime covariance to the compiler, leading to additional unsafe code for lifetime transmutation (though confined as an implementation detail). These lifetimes also proved “infectious,” necessitating the propagation of complex safety semantics into model types storing Property fields.

This complexity largely stemmed from efforts to avoid cloning values into callbacks. However, making these types Clone and storing static-lifetime callbacks ultimately proved beneficial for significantly improving code maintainability.

Threading and Thread Safety

As previously noted, the threading model dictates that interactions with UI implementations occur exclusively on the main thread. This includes updating data bindings, as UI implementations may have registered callbacks on them. While executing all operations on the main thread is possible, it is generally preferable to offload as much work as possible from the UI thread, even for non-blocking tasks (though sending crash reports will be blocking). The aim is for business logic to default to execution off the main thread, preventing UI freezes. This can be ensured through careful design.

The simplest method to ensure this behavior involves encapsulating all business logic within a single (non-Clone, non-Sync) type, referred to as Logic, and constructing the UI and its state (e.g., Property values) in a separate type, called UI. The Logic value can then be moved to a distinct thread, guaranteeing that UI cannot directly interact with Logic, and vice versa. Communication is still necessary, but it is always delegated to the thread owning the respective values, rather than direct interaction between values.

This is achieved by creating an enqueuing function for each type and storing it within the opposing type. Such a function receives boxed functions to execute on the owning thread, which obtain a reference to the owned type (e.g., Box<dyn FnOnce(&T) + Send + 'static>). This setup is straightforward: for the UI thread, it corresponds to the previously discussed invoke method of the UI implementation. The Logic thread simply runs a loop, retrieving these functions and executing them on the owned value (they are enqueued and passed via an mpsc::channel). Consequently, each type can asynchronously invoke methods on the other, with the assurance that they will execute on the appropriate thread.

An earlier iteration employed a more complex scheme involving thread-local storage and a central type responsible for both thread creation and function delegation. However, for the fundamental use case of two threads delegating tasks to each other, the design was simplified to its essential components, significantly reducing code complexity.

Localization

A significant advantage of this rewrite was the opportunity to modernize the crash reporter’s localization to align with current tooling. Most other parts of Firefox utilize Fluent for localization. Integrating Fluent into the crash reporter provides a more consistent and predictable experience for localizers, eliminating the need to learn multiple localization systems (the crash reporter was among the last components using the older system). Its adoption in the new codebase was straightforward, requiring only minimal additional code to extract localization files from the Firefox installation during crash reporter execution. In scenarios where these files are inaccessible, en-US definitions are directly bundled within the crash reporter binary.

The UI Implementations

Detailed discussion of the implementations will be brief, but a summary of each is warranted.

Linux (GTK)

The GTK implementation is arguably the most direct and concise. Bindgen is used to generate Rust bindings for the necessary GTK functions, thereby avoiding the inclusion of external crates. Subsequently, the corresponding GTK functions are invoked to configure the GTK widgets as defined in the model (which was designed to reflect GTK concepts).

Given GTK’s modern design and human-centric development (unlike some platforms reliant on automated tools), few significant challenges or unusual behaviors arose during implementation.

Several features enhance memory safety and correctness. A collection of traits simplifies attaching owned data to GObjects, ensuring data validity and proper deallocation upon GObject destruction. Additionally, specific macros establish the connection between GTK signals and the data binding types.

Windows (Win32)

The Windows implementation presented significant challenges, largely due to the infrequent use of Win32 GUIs today and the API’s age. The windows-sys crate, already included in the codebase for other Windows API interactions, provides access to API bindings. This crate is generated directly from Microsoft’s Windows function metadata, and its bindings are generally comparable to those bindgen might produce, though potentially more accurate.

Several obstacles had to be addressed. The Win32 API lacks layout primitives, necessitating the manual implementation of high-level layout concepts for graceful resizing and repositioning. Additionally, numerous extra API calls were required to achieve a visually acceptable GUI, including correct window colors, font smoothing, and high DPI handling. Surprisingly, the default font was a poor-quality bitmapped font instead of the modern system default, requiring manual retrieval and setting of the system’s preferred font.

A collection of traits assists in creating custom window classes and managing associated data for class instances. Additionally, wrapper types and types are employed to ensure proper management of handle lifetimes and perform type conversions (primarily between String and null-terminated wide strings), adding an extra layer of safety to the API interactions.

macOS (Cocoa/AppKit)

The macOS implementation presented its own complexities, largely because macOS GUIs are predominantly developed with Xcode, involving substantial automated and generated components like nibs. Bindgen was again used to generate Rust bindings, specifically for the Objective-C APIs found in macOS framework headers.

Unlike Windows and GTK, standard keyboard shortcuts (e.g., Cmd-C, Cmd-Q) are not automatically provided when developing a GUI without tools like Xcode, which typically generates them. To ensure these expected user shortcuts, the application’s main menu, which controls keyboard shortcuts, required manual implementation. Runtime setup, such as creating Objective-C autorelease pools and bringing the window and application (distinct concepts) to the foreground, also needed attention. Even the invoke method, designed to call a function on the main thread, had subtleties, as modal windows utilize a nested event loop that would not process queued functions under the default NSRunLoop mode.

Simple helper types and a macro were developed to streamline the implementation, registration, and creation of Objective-C classes from Rust code. This was applied to create delegate classes and subclass controls for the implementation (such as NSButton), facilitating safe memory management of Rust values underlying the classes and accurate registration of class method selectors.

The Test UI

Testing will be covered in the subsequent section. The testing UI is straightforward, not creating a graphical interface but enabling direct interaction with the model. When tests are active, the ui! macro supports additional syntax to optionally assign a string identifier to each element. These identifiers are used in unit tests to access and interact with the UI. Data binding types also include extra methods for tests to easily manipulate values. This UI facilitates simulating actions like button presses and field entries, ensuring expected UI state changes and simulating system side effects.

Mocking and Testing

A key objective of the rewrite was to incorporate tests into the crash reporter, as the previous codebase significantly lacked them, partly due to the inherent difficulty of unit testing GUIs.

Mocking Everything

The new codebase allows for mocking the crash reporter, irrespective of whether tests are being executed (though it is always mocked during tests). This capability is crucial, as mocking enables manual execution of the GUI in various states to verify the correctness and rendering quality of UI implementations. The mocking system extends beyond crash reporter inputs (such as environment variables and command line parameters) to include all side-effectful standard library functions.

This is achieved by including a std module within the crate and consistently using crate::std throughout the rest of the code. When mocking is disabled, crate::std behaves identically to ::std. However, when enabled, a set of custom-written functions are used instead, which mock the filesystem, environment, external command launching, and other side effects. Crucially, only the minimum required functions are mocked, ensuring that if new functions from std::fs, std::net, etc., are introduced, the crate will fail to compile with mocking enabled, thereby preventing overlooked side effects. While this might seem like a substantial undertaking, the amount of the standard library requiring mocking was surprisingly small, and most implementations were quite direct.

With the codebase now utilizing mocked functions, a mechanism for injecting desired mock data (for both tests and normal mocked operations) was necessary. For instance, while the system can return data when a file is read, this data needs to be configurable for different tests. Without delving into excessive detail, this is accomplished using a thread-local store for mock data. This approach avoids modifying existing code to accommodate mock data, requiring changes only where the data is set and retrieved. Programming language enthusiasts may recognize this as a form of dynamic scoping. The implementation enables mock data to be configured with code such as

mock::builder()

.set(

crate::std::env::MockCurrentExe,

"work_dir/crashreporter".into(),

)

.run(|| crash_reporter_main())

in tests, and

pub fn current_exe() -> std::io::Result {

Ok(MockCurrentExe.get(|r| r.clone()))

}

within the crate::std::env implementation.

Testing

The mocking setup and test UI facilitate extensive testing of the crash reporter’s behavior. The final, less automatable aspect of this testing involves verifying that each UI implementation accurately reflects the UI model. This is manually tested using a mocked GUI for each platform.

Beyond this, automated tests can assess how various UI interactions influence the crash reporter’s internal UI state and its environment. This includes verifying invoked programs, network connections, and handling of failures, successes, or timeouts. A mock filesystem is also configured, with assertions in place for various scenarios to check the exact resulting filesystem state upon the crash reporter’s completion. This significantly boosts confidence in current behaviors and guarantees that future modifications will not disrupt them, a critical aspect for such a vital component of the crash reporting pipeline.

The End Product

Naturally, an overview of this development would be incomplete without an image of the crash reporter. The following depicts its appearance on Linux, utilizing GTK. Other GUI implementations maintain the same visual layout but are styled with a native look and feel.

For the time being, the design intentionally mirrors its previous appearance. Therefore, should a user unfortunately encounter it, no visual changes should be apparent.

With the new, refined crash reporter, several pending feature requests and bug reports can now be addressed, including:

- detecting corrupt installations and advising users to reinstall Firefox,

- verifying for faulty memory hardware on the crashing system, and

- utilizing the Firefox network stack for initial crash submission attempts, which respects user network settings such as proxies.

There is anticipation for further iteration and improvement of crash reporter functionality. Ultimately, the ideal outcome is for users never to encounter or utilize it, a goal that is continuously pursued.