KrebsOnSecurity.com marks its 16th anniversary. The past year’s reporting focused heavily on entities that facilitated complex and globally-dispersed cybercrime services, often highlighting instances of accountability.

In May 2024, the history and ownership of Stark Industries Solutions Ltd., a “bulletproof hosting” provider, were scrutinized. This entity emerged two weeks before Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and became a primary staging ground for Kremlin cyberattacks and disinformation. A year later, Stark and its co-owners faced European Union sanctions, but analysis indicated these penalties had limited impact, as the proprietors continued rebranding and transferring network assets to other controlled entities.

In December 2024, Cryptomus, a Canadian-registered financial firm, was profiled as a preferred payment processor for numerous Russian cryptocurrency exchanges and cybercrime service websites targeting Russian speakers. By October 2025, Canadian financial regulators determined Cryptomus had significantly violated anti-money laundering laws, resulting in a record $176 million fine against the platform.

In September 2023, findings were published from researchers who concluded that multiple six-figure cyberheists stemmed from thieves cracking master passwords stolen from the password manager LastPass in 2022. A March 2025 court filing by U.S. federal agents investigating a $150 million cryptocurrency heist indicated they had reached the same conclusion.

Phishing remained a significant topic, with insights into the daily operations of several voice phishing gangs responsible for elaborate and financially devastating cryptocurrency thefts. An article titled A Day in the Life of a Prolific Voice Phishing Crew detailed how one such gang exploited legitimate Apple and Google services to send various communications, including emails, automated calls, and system messages, to users’ devices.

Several reports in 2025 analyzed the persistent SMS phishing, or ‘smishing,’ originating from China-based phishing kit vendors. These vendors facilitate the conversion of phished payment card data into Apple and Google mobile wallets. To counter this, Google has filed at least two John Doe lawsuits against these groups and numerous unnamed defendants, aiming to disrupt the syndicate’s online resources.

January saw research into Funnull, a questionable and extensive content delivery network. Funnull specialized in assisting China-based gambling and money laundering sites to distribute their operations across various U.S. cloud providers. Five months later, the U.S. government sanctioned Funnull, designating it a primary source of ‘pig butchering’ investment/romance scams, as described in a previous report.

In May, Pakistan arrested 21 individuals suspected of working for Heartsender, a phishing and malware distribution service first profiled in 2015. These arrests followed the FBI and Dutch police’s seizure of numerous servers and domains associated with the group. Many of the arrested had been publicly identified in a 2021 report after inadvertently infecting their computers with malware that revealed their real identities.

In April, the U.S. Department of Justice indicted the owners of a Pakistan-based e-commerce company for conspiring to distribute synthetic opioids in the United States. The following month, it was detailed how these sanctioned proprietors are also known for an extensive scheme to scam Western individuals seeking assistance with trademarks, book writing, mobile app development, and logo designs.

Earlier this month, an academic cheating empire, significantly boosted by Google Ads and generating tens of millions in revenue, was examined. This operation has notable connections to a Kremlin-linked oligarch whose Russian university develops drones for Russia’s conflict with Ukraine.

Throughout the year, efforts were made to monitor the world’s largest and most disruptive botnets. These networks launched distributed denial-of-service (DDoS) attacks that were two to three times larger and more impactful than previous record DDoS attacks.

In June, KrebsOnSecurity.com experienced the largest DDoS attack Google had mitigated at that time (the site is a beneficiary of Google’s Project Shield). Experts attributed this attack to Aisuru, an Internet-of-Things botnet that had rapidly expanded since late 2024. A subsequent Aisuru attack on Cloudflare days later nearly doubled the scale of the June incident, and Aisuru was later implicated in another DDoS attack that again doubled the previous record.

By October, the cybercriminals operating Aisuru appeared to have redirected the botnet’s focus from DDoS attacks to a more profitable venture: leasing hundreds of thousands of infected IoT devices to proxy services, enabling cybercriminals to anonymize their traffic.

However, it has recently emerged that some disruptive botnet and residential proxy activity previously attributed to Aisuru was likely the work of those developing and testing Kimwolf, a powerful botnet. Chinese security firm XLab, which first documented Aisuru’s emergence in 2024, recently profiled Kimwolf as potentially the world’s largest and most dangerous collection of compromised machines, controlling approximately 1.83 million devices by December 17.

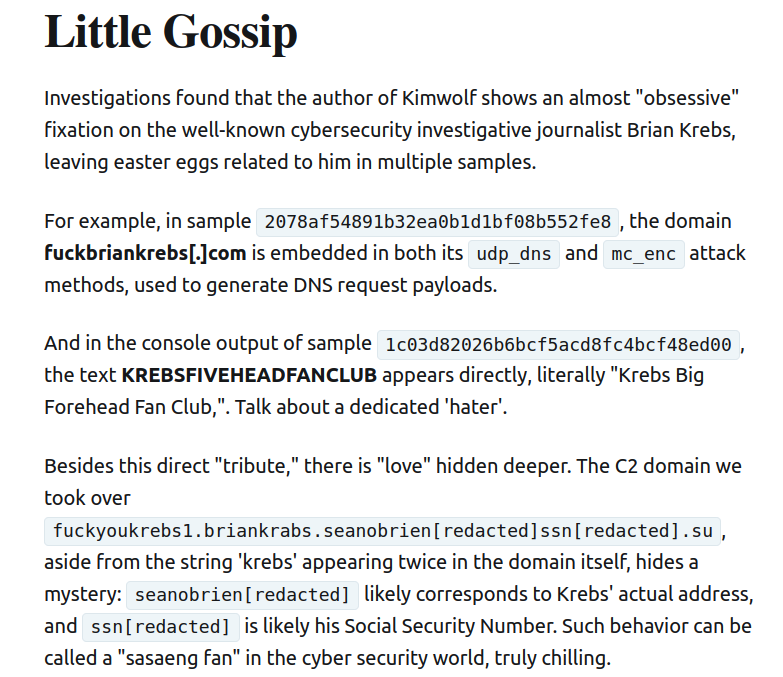

XLab observed that the Kimwolf author displayed an ‘obsessive’ fixation on cybersecurity investigative journalist Brian Krebs, incorporating related ‘easter eggs’ in various locations.

Upcoming stories for 2026 will delve into Kimwolf’s origins, exploring the botnet’s distinctive and highly invasive methods of propagation. The initial report in this series will feature a global security notification regarding devices and residential proxy services inadvertently contributing to Kimwolf’s rapid expansion.