Very few organizations can supply cadmium zinc telluride, a material produced by companies like Kromek.

Undergoing a hospital scan can be a lengthy process, often requiring patients to remain still for extended periods. At London’s Royal Brompton Hospital, lung scans that once took 45 minutes have been reduced to just 15 minutes thanks to a new device installed last year. This efficiency is partly due to advanced image processing technology, but also a remarkable material known as cadmium zinc telluride (CZT).

CZT enables the scanner to generate highly detailed, three-dimensional images of patients’ lungs. Dr. Kshama Wechalekar, head of nuclear medicine and PET, describes the resulting images as “beautiful” and the technology as an “amazing feat of engineering and physics.”

The CZT used in the Royal Brompton Hospital’s scanner was produced by Kromek, a British company. This material is driving a “revolution” in medical imaging, according to Dr. Wechalekar, and its applications extend beyond healthcare to X-ray telescopes, radiation detectors, and airport security scanners, making it increasingly valuable.

Dr. Wechalekar’s team utilizes these advanced lung investigations to identify conditions such as numerous small blood clots in individuals with long Covid or larger pulmonary embolisms. The £1m scanner operates by detecting gamma rays emitted from a radioactive substance injected into patients. Its enhanced sensitivity allows for a significant reduction in the required radioactive dose, by approximately 30%. While CZT-based scanners are not entirely new, large, whole-body systems like this one represent a recent advancement.

Despite its long existence, CZT is notoriously challenging to manufacture. Arnab Basu, founding chief executive of Kromek, notes that developing an industrial-scale production process for the material has been a lengthy endeavor.

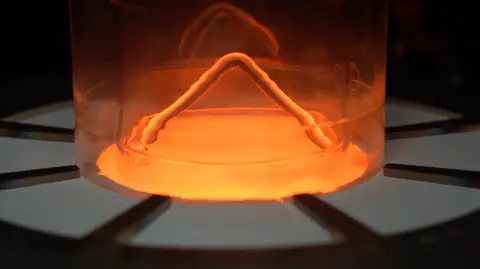

Kromek’s Sedgefield facility houses 170 small furnaces, which Dr. Basu likens to a “server farm.” Inside these furnaces, a specialized powder is heated until molten, then slowly solidified into a single-crystal structure. This intricate process, where atoms are meticulously rearranged and aligned, spans several weeks.

The resulting CZT is a semiconductor capable of detecting minute photon particles from X-rays and gamma rays with exceptional accuracy. Its function is comparable to a highly specialized version of a smartphone camera’s silicon-based image sensor. When a high-energy photon strikes the CZT, it generates an electrical signal by mobilizing an electron, which is then used to form an image. This single-step conversion process is more precise than older, two-step scanner technologies.

Dr. Basu highlights the digital nature of CZT, explaining that it performs a single conversion step, preserving crucial data like timing and the energy of the X-ray hitting the detector. This capability allows for the creation of color or spectroscopic images. Beyond medical applications, CZT-based scanners are currently employed for explosives detection at UK airports and for checked baggage screening in some US airports, with expectations for its integration into hand luggage screening in the coming years.

Special furnaces are required for the intricate process of making CZT.

Acquiring CZT can be challenging due to its specialized nature and limited production. Professor Henric Krawczynski of Washington University in St. Louis has previously utilized the material in space telescopes carried by high-altitude balloons. These detectors are designed to capture X-rays originating from neutron stars and plasma surrounding black holes.

Professor Krawczynski requires extremely thin, 0.8mm pieces of CZT for his telescopes to minimize background radiation and ensure a clearer signal. He expressed the difficulty in obtaining these specific thin detectors, stating a need for 17 new units.

Kromek was unable to supply the CZT to Professor Krawczynski, with Dr. Basu explaining the high demand and the challenge of catering to the unique detector requirements of numerous research organizations. For Professor Krawczynski, this is not a critical issue, as he may use existing CZT or an alternative material, cadmium telluride, for his upcoming mission.

However, the mission faces other obstacles; its scheduled December launch from Antarctica is uncertain due to the US government shutdown.

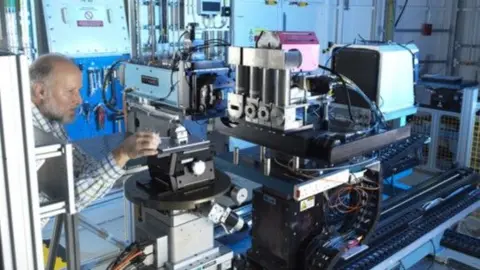

CZT is slated for use in an upgrade of the Diamond Light Source facility.

CZT is also widely utilized by other scientific researchers. In the UK, the Diamond Light Source research facility in Oxfordshire is undergoing a substantial half-billion-pound upgrade. This enhancement will significantly improve its capabilities through the integration of CZT-based detectors.

The Diamond Light Source operates as a synchrotron, accelerating electrons around a massive ring at near light speed. Magnets cause these electrons to emit X-rays, which are then channeled into beamlines for material analysis. Recent experiments at the facility have included investigating impurities in melting aluminum, with the aim of improving recycled metal forms.

The upgrade, expected to conclude by 2030, will generate considerably brighter X-rays, rendering current sensors inadequate. Matt Veale, group leader for detector development at the Science and Technology Facilities Council, a key stakeholder, emphasizes the necessity of advanced detection: “There’s no point in spending all this money in upgrading these facilities if you can’t detect the light they produce.” Consequently, CZT has been selected as the preferred material for these new detectors.