Before the 20th century, accurately detecting pregnancy was challenging. Methods like observing missed menstrual cycles, a developing baby bump, or a fetal heartbeat were only effective several months into gestation. Historical accounts detail various pregnancy tests, though none met modern reliability standards. For instance, an ancient Egyptian papyrus described a test involving the germination of cereal grains with a potentially pregnant person’s urine. While this might have some validity given current knowledge of pregnancy hormones, variations in these ancient texts make their evaluation difficult.

During the 19th and 20th centuries, the nascent field of endocrinology, the study of hormones, offered new avenues for research. This period saw a shift from anatomical studies to investigating the unseen influence of “internal secretions” and “juices” on bodily functions. Early endocrinological experiments were often rudimentary, typically involving injecting fluids from one organism into another to observe the effects.

Charles-Édouard Brown-Séquard, a pioneering endocrinologist, anticipated the existence of hormone chemicals. In 1889, he published results from a self-experiment where he injected an elixir derived from dog or guinea pig testicular blood, semen, and crushed testicular juice. Brown-Séquard claimed these injections revitalized him with youthful vigor, though his findings have rarely been replicated.

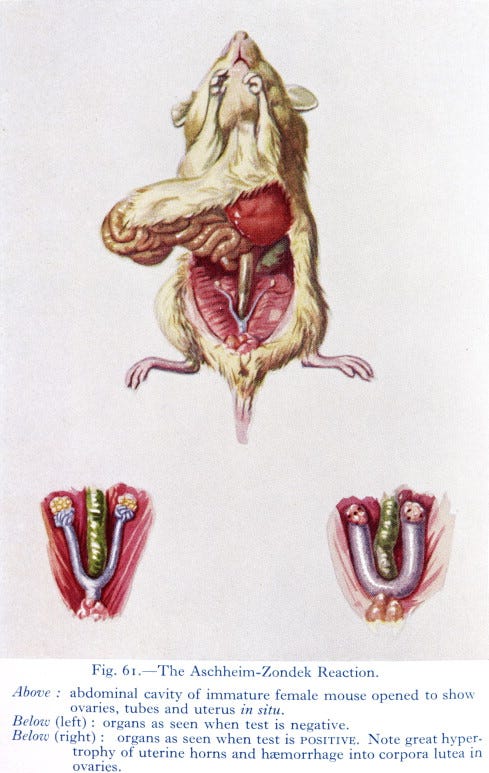

Following similar investigative approaches, Berlin-based doctors Selmar Aschheim and Bernhard Zondek developed an early pregnancy test in 1928. This method involved injecting patient urine into laboratory mice. After several days, the mice were euthanized and dissected to examine their ovaries; the presence of “ovarian blood spots” indicated pregnancy in the urine donor. Both physicians, who were Jewish, later had to flee Germany due to the rise of the Nazis.

In the U.S., Maurice Friedman adapted this technique for rabbits, which could accommodate larger urine volumes, offered more reliable ovulation patterns, and were generally easier for clinical centers to house. His “rabbit test,” introduced in 1931, became the American standard for several years. However, both the mouse and rabbit tests shared significant drawbacks: they required several days for results, and the animals needed to be euthanized or undergo surgery to check for ovulation.

The Aschheim-Zondek reaction, as published in “A text-book of midwifery for students and practitioners” in 1934. Credit: Olszynko-Gryn J. (2014).

The Aschheim-Zondek reaction, as published in “A text-book of midwifery for students and practitioners” in 1934. Credit: Olszynko-Gryn J. (2014).

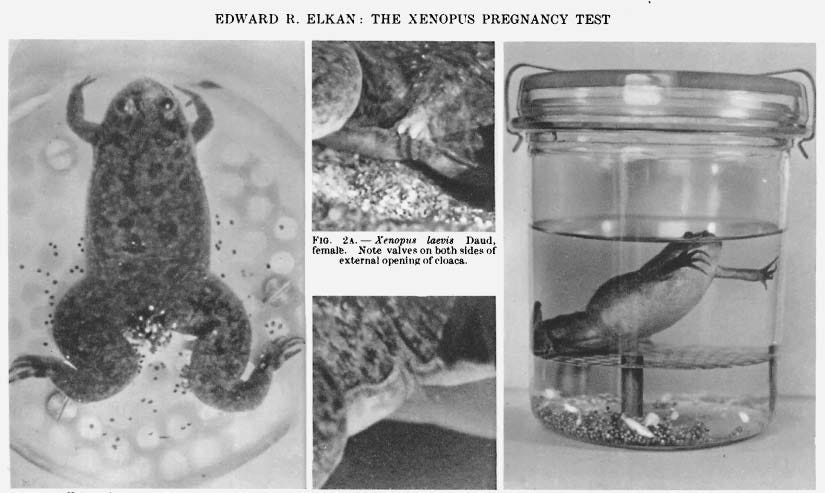

Around the same period, British scientist Lancelot Thomas Hogben, based in South Africa, injected ox pituitary extract into an African clawed frog, Xenopus laevis, while researching hormonal influences on ovulation. Within hours of the injection, the frog laid hundreds of eggs, a significant discovery. Inspired by this, Hogben’s former students, Hillel Shapiro and Harry Zwarenstein, showed that these African frogs were far more suitable for pregnancy tests than mice or rabbits. A decade later, Hogben asserted that the idea to use Xenopus for pregnancy testing was his own, and that Shapiro and Zwarenstein’s work had actually hindered its clinical adoption. The two scientists, however, disputed his account.

Images from a 1938 article in the British Medical Journal, explaining how to use Xenopus frogs to test for pregnancy. Credit: Lisa Jean Moore

Images from a 1938 article in the British Medical Journal, explaining how to use Xenopus frogs to test for pregnancy. Credit: Lisa Jean Moore

These frogs reliably ovulated within 18 hours of receiving a pregnant person’s urine sample, laying easily visible eggs year-round. This new “bioassay” was faster than the rabbit test and left the animal unharmed for subsequent use. News of this method spread rapidly, leading to a widespread adoption of ovulating Xenopus frogs in biological institutions.

Modern pregnancy tests no longer require animals like rabbits or frogs, thanks to the discovery of the specific “pregnancy hormone” (chorionic gonadotropin, or hCG) and the development of lateral flow detection devices. However, the extensive use of Xenopus laevis (and related species) for pregnancy testing likely solidified their role in broader scientific research.

Xenopus frogs exhibit a unique, almost serene presence. Their lidless eyes protrude from their flat heads, and they often remain still in the water, observing their surroundings, when not engaged in feeding, swimming, or mating. Lacking tongues, they open their mouths and

with their front feet to consume food. These front feet also enable them to grip females during mating, while their webbed back feet, featuring distinctive black claws on the last three toes, are used for swimming. These unusual appendages gave rise to their name, “Xenopus,” meaning “strange-footed.”

The sudden proliferation of Xenopus in laboratories during the 1930s and 40s might appear fortuitous for biologists, but frogs were already established subjects in research. Long before Xenopus frogs served as “obstetrical consultants,” numerous other frog species contributed significantly to developmental biology.

Their widespread use stemmed from convenience: frogs are relatively easy to locate, capture, and maintain, a fact familiar to anyone who grew up near a pond. They also lay numerous eggs, which are typically larger than most fish eggs and lack the hard shells of bird eggs, making them ideal for studying embryonic development.

In the 18th century, Italian scientist Lazzaro Spallanzani conducted some of the most notable early frog experiments. Spallanzani, also credited with discovering bat echolocation and the chemical nature of digestion, demonstrated that fertilization could occur outside the female body by brushing unfertilized eggs with frog sperm. He later confirmed this in mammals through the successful in vitro fertilization of a dog.

However, one of his most memorable experiments demonstrated that semen was specifically responsible for fertilization. Using a negative control, Spallanzani dressed male frogs in miniature taffeta breeches, meticulously sewn for their tiny legs, to prevent semen from reaching the eggs during mating. The outcome, he recorded, was as anticipated: “the eggs are never prolific [e.g., fertilized], for want of having been bedewed with semen, which sometimes may be seen in the breeches in the form of drops.” Spallanzani, despite the whimsical nature of the frog breeches, was pleased with the idea and resolved to implement it.

A statue of Lazzaro Spallanzani examining a frog. Scandiano, Italy. Credit: Maxo

A statue of Lazzaro Spallanzani examining a frog. Scandiano, Italy. Credit: Maxo

For the next century, European scientists continued to advance the field of embryology through experiments with amphibian eggs. These studies typically utilized locally available species, such as frogs from the genus Rana, common in Europe, Asia, and North America. It was not until a century and a half after Spallanzani’s experiments that American and European biologists gained access to a plentiful supply of Xenopus eggs, largely due to their application in fertility testing.

The characteristics that made African clawed frogs suitable for pregnancy testing also established them as excellent laboratory models; they thrive in captivity. Xenopus are entirely aquatic species with relatively simple requirements compared to most amphibians. While they breathe air and occasionally use their nostrils, they can drown if left underwater while anesthetized, requiring a platform during surgical recovery. They consume a wide variety of food and can survive in tap water, though they remain sensitive to water conditions, particularly metal content. These frogs can live for up to twenty years, and a single brood can produce hundreds to thousands of eggs.

For scientists, the eggs of these frogs are often more compelling than the adults. Approximately one-tenth the size of a marble yet clearly visible, these two-toned eggs feature a dark side and a light side, resembling a Poké Ball. The contrast between these sections, with a grey crescent in between, intensifies after fertilization as pigmentation concentrates at the sperm entry point. The darker half, known as the “animal” pole, divides into smaller cells more rapidly, appearing more “animated” compared to the “vegetal” pole, the lighter half characterized by dense yolk.

Today, many videos demonstrate that observing the early stages of cellular division in Xenopus eggs requires no special dyes or equipment beyond, perhaps, a magnifying lens. Extensive research by numerous scientists has since mapped which organs develop from these initial cell divisions.

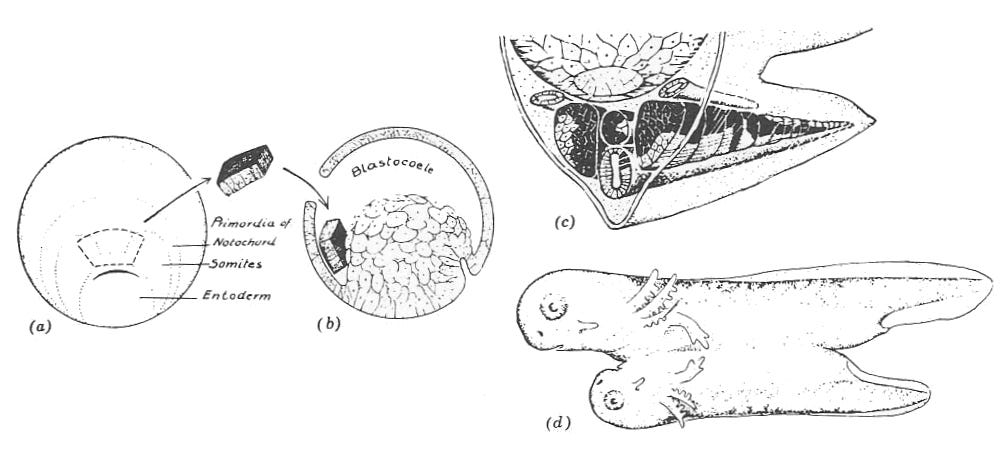

Beyond their visual characteristics, frog eggs are valuable research subjects due to the ease with which their embryos can be manipulated. Eggs can be poked, prodded, or even completely separated while still retaining the capacity to develop into tadpoles. A notable experiment in early embryology, performed by Hans Spemann and his student Hilde Mangold in the 1920s, was initially conducted on newts but can be

: if a small piece of tissue is removed from one amphibian embryo and attached to a second, this transplanted cell cluster will develop alongside the “donor” egg, resulting in a tadpole with two fully formed heads. Spemann received the Nobel Prize in 1935 for this work, but Mangold, tragically, died at age 26 in a kitchen accident before her doctoral research paper was published.

If the dorsal lip from one embryo is grafted onto a second embryo, one can make tadpoles with two heads. Image from Spemann-Mangold, 1922.

If the dorsal lip from one embryo is grafted onto a second embryo, one can make tadpoles with two heads. Image from Spemann-Mangold, 1922.

Spemann and Mangold’s remarkable discovery ignited an international effort to identify the chemical factors governing the “organizer” tissue, as they termed it. However, researchers of that era lacked the necessary tools to fully uncover the secrets of these organizer cells. While it was generally understood that chromosomes within the cell’s nucleus controlled biological traits, the mechanism by which these chromosomes gave rise to genes remained unknown.

This changed in 1953 with Watson and Crick’s seminal papers, which described the structure of the DNA molecule and proposed a mechanism for gene inheritance. The subsequent decade saw the unraveling of the genetic code, primarily through studies on simple models like bacteria, viruses, and yeast. Yet, it was a Xenopus experiment that most strikingly demonstrated that even adult animal cells contained the complete genetic information required to recreate an entire organism.

In 1968, building on experiments by Robert Briggs and Thomas King that demonstrated successful nuclear transfer between cells, developmental biologist John Gurdon extracted the nucleus from an adult frog cell and injected it into an enucleated egg. This egg, now containing DNA from an adult “parent,” developed into a normal tadpole and subsequently an adult frog, possessing all the diverse cell types of a typical animal. This new frog was a “clone,” a term derived from the Greek word for “twig,” signifying its growth from an adult clipping rather than a seed. Early animal cloning attempts had very low success rates, often requiring dozens to hundreds of tries for a cloned egg to reach adulthood. Half a century later, John Gurdon published papers explaining this, showing that while nearly every adult cell contains the entire genome, it retains cell-specific “memory” through mechanisms like histone modifications. While Dolly the sheep, cloned in 1996, became famous as the first cloned mammal, the first animal cloned from an adult cell was actually a Xenopus frog, nearly three decades prior.

Today, when molecular biologists discuss “cloning work,” they typically refer to the cloning of specific genes, not the creation of identical adult animals. This involves synthesizing or copying a gene’s sequence (the unique combination of DNA chemical letters) and amplifying it by leveraging the rapid proliferation and gene-copying abilities of E. coli bacteria. This fundamental technique, enabling bacteria to express a eukaryotic gene, traces back to the successful cloning of a Xenopus gene in 1974.

Genetic cloning became feasible through three key discoveries: restriction enzymes, which act as molecular scissors to cut DNA at specific sequences; ligases, capable of rejoining these fragments into new configurations; and the concept of incorporating antibiotic resistance genes alongside the cloned gene to identify successful constructs using antibiotics. Herb Boyer of UC San Francisco, who purified the restriction enzyme EcoRI and later founded Genentech (considered the world’s first biotechnology company in 1976), conceived this idea with Stanford bacterial geneticist Stanley Cohen during a research discussion at a Hawaiian deli in 1972. After transforming bacteria with their engineered plasmids, Boyer recalled his emotional reaction upon seeing the results: “I went to look at the gels in the darkroom, and there it was. It actually brought tears to my eyes, it was so exciting.”

Boyer and Cohen, with their colleagues, soon advanced beyond merely introducing bacteria-derived genes into other bacteria. In 1974, their team successfully spliced the Xenopus ribosomal RNA gene into E. coli cells. This specific frog gene was chosen for its thorough characterization and availability in large quantities. This groundbreaking achievement proved that bacteria could be induced to read and copy genes from organisms separated by a billion years of evolution, thereby establishing the groundwork for genetic engineering, synthetic biology, and biomanufacturing.

Despite its advantages, Xenopus laevis presented challenges. Although favored for fertility testing and embryology, the frog proved less ideal for genetic research because it possesses approximately four copies of each gene, rather than the typical two (one from each parent). This chromosomal complexity, while not unique in nature, made sequencing laevis genomes considerably more difficult due to the presence of four similar, but not identical, chromosome sets. A complete laevis genome assembly was not released until 2016, lagging a decade or more behind other model organisms like Mus musculus (mouse) and Rattus norvegicus (lab rat), or agricultural animals such as Bos taurus (cow) and Gallus gallus (chicken).

Despite the limited understanding of Xenopus genetics, biologists in the 1980s discovered another innovative application for Xenopus eggs. Eggs are essentially large cells, providing researchers with an abundant source of easily manipulated cellular material. Similar to how young frog embryos remain viable after needle manipulation, the cellular components of frog eggs maintain biological activity even after being gently crushed and separated from their yolks, chromosomes, and heavier elements through centrifugation. This cellular extract could be produced in large volumes, and the resulting mixture of proteins and organelles would still perform many complex cellular operations within a more observable and controllable system.

Xenopus laevis. Credit: Brian Gratwicke

Xenopus laevis. Credit: Brian Gratwicke

These systems, while not whole cells, contain nearly all intracellular components, making them particularly valuable for deciphering the intricate mechanisms of cell division. Xenopus egg extracts were crucial for identifying proteins that regulate the cell cycle, understanding the precise arrangement of chromosomes during division, observing the self-assembly of microtubules that guide and move chromosomes, and elucidating the role of small messenger proteins, known as Rans, in various cellular activities. These discoveries were facilitated by the easy visualization of the cell-free extract components and their exposed nature, allowing direct introduction or removal of chemicals without membranous barriers.

Throughout the 1980s and 1990s, scientists seeking to conduct genetic research on Xenopus frogs without the genetic complexities of X. laevis explored related species. By the late 1990s, they identified Xenopus tropicalis, a species offering many advantages of X. laevis but possessing only two sets of chromosomes instead of four. While some laboratories transitioned to X. tropicalis, many groups with established X. laevis protocols were hesitant, particularly because Xenopus tropicalis requires different housing and handling. Additionally, Xenopus tropicalis frogs are smaller than X. laevis, with smaller eggs and brood sizes. Fortunately, genetic engineering has advanced significantly, and today both X. laevis and X. tropicalis are widely utilized in biological research.

While knowledge has vastly expanded since the 1930s when Xenopus frogs first appeared in research labs, they continue to address fundamental biological questions, serve as vertebrate animal models for drug development and testing, and contribute to experiments whose full implications may only be realized in the future. Due to their historical significance in fertility and embryology, four African clawed frogs even became astronauts in 1992, traveling aboard the Space Shuttle Endeavour to investigate reproduction and development in zero gravity. These frogs successfully laid eggs and produced viable offspring during their space mission. Fortunately, no one required them to wear pants.