Dhaka’s streets tell a story of transition. Where pedal rickshaws once dominated the city’s intricate network of narrow lanes and busy intersections, battery-powered variants now weave through traffic with increasing prevalence. This shift represents a fundamental restructuring of urban mobility, livelihoods, and city planning challenges.

Innovision Consulting, Bangladesh’s leading management consulting firm, recently released a comprehensive study titled Urban Mobility Study: From Battery to Pedal – Rickshaws in Transition, examining this transformation. Based on surveys of 384 rickshaw drivers, 392 passengers, and 63 garage owners across Dhaka North and South City Corporations, the report offers fascinating insights into one of the city’s most visible yet poorly understood economic sectors.

Here are several key takeaways from the report that highlight the complexity behind Dhaka’s evolving transportation landscape. The full report can be accessed here.

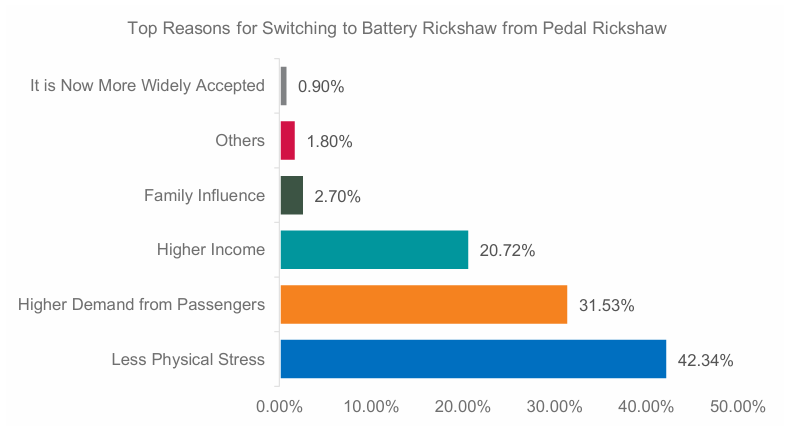

1. The Motivation is Physical, Not Just Financial

When asked why they switched from pedal to battery, “42.34% of drivers cited reduced physical strain, the single largest factor.” Passenger demand came second at 31.53%, with higher income third at 20.72%.

This reveals something often overlooked in economic analyses: the brutal physical toll of driving a pedal rickshaw. For aging workers or those seeking sustainable long-term employment, battery rickshaws offer dignity alongside income.

This dignitary aspect warrants greater consideration in policy discussions. When regulators discuss “cleaning up the streets” or “modernizing transport,” they rarely acknowledge that they are addressing people’s bodies, the knees, backs, and cardiovascular systems that pedal rickshaws can damage over decades of work.

Battery rickshaws are not just about earning more; they are about surviving longer in the profession. Any policy that forces workers back to pedal rickshaws is effectively mandating bodily harm for aesthetic or administrative convenience.

2. Registration is Almost Non-Existent; But is That Actually the Problem?

The registration numbers are stark: “97.4% of battery rickshaws operate unregistered, compared to 86% of pedal rickshaws.” According to official data cited in the report, “there are 1,82,630 registered pedal rickshaws under [Dhaka South City Corporation’s] jurisdiction and there are 30,000 rickshaws under the Dhaka North City Corporation’s jurisdiction. However, this data is not up-to-date.”

Without registration, there is no accountability, no maintenance standards, no driver licensing, and no meaningful regulation. The sector exists almost entirely in the shadows of the formal economy.

However, it is important to question whether formalization necessarily improves outcomes. Bangladesh’s vehicle registration systems are notoriously corrupt, slow, and expensive. The BRTA is not known for efficient, citizen-friendly service.

The question is not whether rickshaws should be registered, but whether the existing registration systems are fit for purpose. If formalization means drivers spending days at BRTA or other government offices, paying unofficial fees to expedite processes, and facing harassment from those who view registration as a revenue opportunity rather than a public service, then the situation might worsen.

Some argue that a lack of regulation might be preferable to excessive regulation implemented through Bangladesh’s current administrative infrastructure. This pattern has been observed repeatedly: well-intentioned rules become mechanisms for extraction, driving more activity underground rather than integrating it into the formal economy.

3. Passengers Choose Efficiency Over Safety and Know Exactly What They’re Doing

An interesting paradox emerges: passenger preference splits roughly 50-50 between battery and pedal rickshaws (50.77% prefer battery, 49.23% prefer pedal), yet 74.23% actually use battery rickshaws for daily commutes.

The reasons are clear from the data. Of passengers who prefer battery rickshaws, “82% stated that it was more time efficient.” Meanwhile, of those who prefer pedal rickshaws, “93% cited safety.”

People are aware that battery rickshaws can be more dangerous, but they cannot afford the time cost of the safer alternative. This is not ignorance; it is rational decision-making under constraints.

This revealed preference holds significant implications for policy. When regulators decide what is “best” for people, they often overlook these constrained choices. A middle-class policymaker who drives to work might find it easy to prioritize safety over speed. A garment worker who loses wages for being late understands the calculation differently.

This does not mean abandoning safety improvements. It means recognizing that people are making informed tradeoffs, and policy should enhance choices rather than eliminate them. The goal should be to provide safer battery rickshaws, not just pedal rickshaws or no options at all.

4. The Primary Users are Lower-Middle Income Workers, The Policy-Invisible Class

The core user base consists of adults aged 18-34 (52%) with monthly household incomes between BDT 20,001-50,000. The report notes that “approximately 79% of the passengers within this income bracket are aged between 18 and 44 years.”

These are not the city’s poorest residents, but they are not wealthy enough for private transport either. The report found that “Approximately 55.36% of respondents with a monthly household income between BDT 10,001 and 50,000 reported spending BDT 10–110 per day on rickshaw rides for personal travel needs. This suggests that individuals within this income bracket represent the primary and most significant commuter segment for this mode of transportation. Moreover, as income increases, the number of passengers spending BDT 10-109 and BDT 110-209 increases as well until the monthly income of the passengers reaches the range of BDT 20,001 – 30,000. Beyond BDT 30,000, passengers become less dependent on using rickshaws to travel, as income and expense begin to have an inverse relationship. This shows that as income increases, the number of passengers willing to spend on rickshaws decreases.”

This income band is often politically invisible. Too “well-off” for poverty programs, too poor for car-centric infrastructure, these are the people who make Dhaka function: office workers, shop employees, small business owners, students.

When regulations are implemented without considering their constraints, it effectively taxes the city’s working backbone. The wealthy adjust (they take Ubers), the poor endure (they walk), but the lower-middle-income workers, who are striving for economic advancement, are squeezed hardest.

5. Rickshaws are First-Mile/Last-Mile Connectors, filling Transit Gaps

The usage data reveals rickshaws’ true role in Dhaka’s transport ecosystem. Top uses include “going to work (17.34%), commuting to public transport (13.77%), and children’s school runs (9.94%).”

The report emphasizes: “Nearly two-thirds of passengers use rickshaws for short trips of 1–3 km, while over one-third rely on them for longer-distance travel.”

Rickshaws do not compete with buses or CNGs for long hauls. They solve the “last mile problem” that plagues public transit systems worldwide, connecting homes to transit hubs and workplaces to main roads.

This functional role should fundamentally shape regulation. The report’s recommendation for “zone-based operation regulations (allowing battery rickshaws only in alleys/inner roads)” makes sense precisely because that is already what most passengers use them for.

However, concerns arise regarding implementation. “Allowing only on inner roads” sounds reasonable until one attempts to define which roads qualify, and then enforce those definitions across thousands of narrow, unmarked streets. Such regulatory ambiguity can become another opportunity for harassment.

This has been observed with street vendors, small manufacturers, and informal services. Vague rules that grant enforcers discretion often become mechanisms for extraction. If clear, map-based regulations that drivers can follow with minimal official interaction cannot be written, then they should not be implemented at all.

6. Public Opinion Demands Regulation, Not Bans. But What Kind of Regulation?

The report found that “79% of passengers support stricter regulation of battery rickshaws.” But when asked what the government should actually do, 78.06% favor zone-based regulation over outright bans.

The most popular approaches: “allow them only on inner roads, not on main roads (33.93%), require valid driver licenses (22.19%), and impose speed restrictions (21.94%). Only 21.94% support complete prohibition.”

This reflects sophisticated public opinion, recognizing both the service value and safety concerns, seeking balanced solutions rather than blanket bans. The report accurately characterizes this: “support for stricter regulation of battery rickshaws is high (79%), rather than an outright ban.”

However, caution is needed when interpreting “support for regulation” as a blank check. The public desires better, safer service; they are not requesting bureaucratic harassment of drivers or corruption-enabling administrative processes.

The second-order consequences of regulation are immensely important. When licenses are required, who issues them? How long does it take? What unofficial fees emerge? When speed restrictions are imposed, who enforces them? With calibrated equipment or arbitrary judgment? When allowed roads are designated, who decides? With community input or administrative fiat?

Bangladesh’s public policy record suggests these details often get captured by rent-seeking interests, transforming reasonable regulations into unreasonable burdens. Policymakers must be mindful of this challenge, considering not just the intended effects of regulations, but how they will actually function within Bangladesh’s administrative reality.

7. Garage Owners are Gradually Transitioning, and They’re the Key to Change

The 63 garage owners surveyed have a median of 18 years in the business; these are experienced entrepreneurs, not opportunistic newcomers. The report notes: “Garage owners act as the backbone of this informal economy, with a median of 18 years in the trade.”

Collectively, they own 1,400 pedal rickshaws versus 975 battery units. But the transition is underway: “35% of the garage owners surveyed transformed their previously owned pedal rickshaws to battery rickshaws” at a weighted average cost of BDT 62,230 per vehicle.

Currently, “62% of garage owners prefer battery rickshaws over pedal rickshaws,” citing higher demand, greater income potential, and operational flexibility.

This is one of the most actionable insights in the entire report. Garage owners possess capital, experience, and long-term stakes in the sector. They are natural partners for formalization, provided incentives are properly aligned.

The report recommends that “NGOs & MFIs could provide the ‘affordable credit’ required to incentivize the transition from pedal to battery rickshaws. Furthermore, garage owners can be offered this credit only if they purchase battery rickshaws produced through the standardized manufacturing procedure.”

This approach makes sense, but the details are crucial. “Standardized manufacturing” could mean genuine safety improvements, or it could mean politically-connected manufacturers gaining a captive market. “Affordable credit” could ease formalization, or it could create new debt dependencies.

A more effective approach might involve carrots, not sticks, to make formal, standardized operations more profitable than informal ones, rather than simply making informal operations illegal. However, this requires the government to deliver tangible value: faster registrations, protection from arbitrary enforcement, access to designated parking and charging, and potentially even preferential routes or hours.

If formalization merely entails more costs without more benefits, garage owners will likely remain informal and use their resources to evade enforcement, while drivers bear the costs.

8. The Conversion Economics Reveal Market Momentum

An insight emerges from combining data points: the report shows that converting a pedal rickshaw to battery power costs approximately BDT 62,230, and this is “typically financed via MFIs.”

However, new battery rickshaws cost BDT 35,000-200,000. This suggests that the conversion route, which involves taking existing pedal rickshaw frames and adding motors, is actually more expensive than purchasing purpose-built battery rickshaws at the lower end of the price range.

Why would owners choose this? Possibly because they already own the pedal rickshaws (sunk cost), have established relationships with specific fabricators, or face credit constraints that make BDT 62,230 in conversion loans easier to obtain than BDT 100,000+ for new vehicles.

This also suggests that the informal assembly market may be inefficient and potentially produces lower-quality vehicles. Purpose-built battery rickshaws from standardized manufacturers might actually be cheaper and safer than ad-hoc conversions.

This creates a policy opportunity: instead of banning conversions, standardized options could be made more attractive through credit access or registration preferences. This would allow the market to shift toward quality rather than being forced through prohibition.

9. The Charging Infrastructure Gap is Real but Solvable

The report notes that among challenges faced by garage owners, “more than 60% commonly struggle with frequent need for repairs, battery costs, and replacements.” It also mentions “charging infrastructure gaps, such as the lack of accessible charging stations, also limit operational efficiency.”

This presents a positive opportunity for policymakers, as infrastructure is something the government can directly provide without becoming entangled in complex enforcement issues.

Designated charging stations, potentially operated through Public-Private Partnerships (PPPs) or utility company tie-ins, could be a genuinely helpful intervention that does not require harassing drivers. It would also create visibility into fleet size and usage patterns, facilitating registration through service provision rather than bureaucratic decree.

This approach appears to be a viable model to pursue: make formalization attractive by solving real problems that the informal sector cannot address on its own. Need charging? Register your vehicle. Need parking? Show your license. Need access to better roads during certain hours? Comply with safety standards.

This flips the logic from punishment to incentive, creating systems where compliance is the path of least resistance rather than the greatest hassle.

10. The Safety-Income Tradeoff isn’t Actually Fixed

One of the most important insights comes from combining the accident and income data. Battery rickshaws have higher accident rates and severity, but also higher income potential for owners. Pedal rickshaws are safer but physically destructive and lower-earning.

However, this tradeoff is not technologically determined; it is a function of current vehicle design, driver training, and road infrastructure. The report’s recommendation for “standardized vehicle design” recognizes this.

Speed governors, better brakes, improved stability, mandatory lights and reflectors, and driver training on defensive techniques could all enhance battery rickshaw safety without eliminating their economic advantages.

The question is whether regulation mandates these improvements in ways that actually happen, or in ways that merely create compliance costs without safety benefits.

This situation is reminiscent of helmet law debates in many South Asian countries. Mandatory helmets are obviously beneficial for safety, but enforcement often leads to police taking bribes rather than ensuring helmet use. The regulation exists, compliance is low, rent-seeking is high, and safety does not actually improve.

It is crucial to design for the political economy that exists, not the one desired. In Bangladesh’s current governance context, this means simple, verifiable standards that are difficult to fake and hard to selectively enforce. “Your rickshaw has working brakes and lights” is enforceable. “Your rickshaw meets 47 different specifications requiring expert assessment” becomes an extortion opportunity.

11. The Aspiration Data Reveals This isn’t a Terminal Occupation

The report found that “46.88% of pedal drivers and 47.40% of battery drivers desire to drive another vehicle” in the future. Among battery drivers specifically, “40% expressed aspirations to transition to driving motor vehicles.”

The top aspiration for pedal drivers? Battery rickshaws (36.62%). For battery drivers? CNG/Auto-rickshaws (27.69%) and private cars/pickups/buses (15.38%).

This reveals rickshaw driving as a transitional occupation, not a destination. People enter the sector seeking something better than farming or daily labor, but hope to transition into more prestigious, higher-earning transport work.

This information is relevant to discussions about formalization. The goal is not to trap people in rickshaw driving with better regulations; it is to make the sector a functional stepping stone. This implies training that is transferable (defensive driving, traffic rules, customer service), licensing that builds credit history and formal identity, and income levels that allow saving for the next transition.

If regulation makes rickshaw driving more expensive to enter or more difficult to leave, it risks deepening the poverty trap rather than helping people escape it.

12. A Relatively Young Workforce Entering an Old Profession

The demographic shift is striking. Battery rickshaw drivers have a median age of 38 years compared to 42 for their pedal-pushing counterparts. More tellingly, they are better educated, with 32% having completed education beyond grade six, versus 26% of pedal drivers.

This suggests battery rickshaws are attracting a different type of worker: younger, slightly more educated, and likely viewing this as a stepping stone rather than a lifetime vocation. The profession is evolving from a last-resort occupation to something that might offer genuine economic mobility, at least in perception.

This aspect holds more significance than it might initially seem. Education levels in informal transport work often correlate with bargaining power, safety consciousness, and the ability to navigate regulatory systems. A more educated driver workforce could be crucial for any formalization effort. At the same time, it also indicates a challenge in creating higher-value opportunities for human resources.

13. Seasoned Veterans vs. New Entrants

Perhaps the most consequential finding: pedal rickshaw drivers average 15 years of experience, while nearly 60% of battery drivers have less than two years behind the handlebars. The report notes that “43.75% respondents reported having more than 15 years of experience in driving a pedal rickshaw, indicating a long-standing and stable workforce within this segment.”

This creates a safety paradox. The sector is rapidly expanding with operators who lack the street wisdom, traffic navigation skills, and passenger handling experience that comes from years on the road. It is a recipe for accidents, and the data bears this out.

However, careful consideration is needed for policy responses. Driver training programs sound reasonable, but Bangladesh’s history of licensing requirements often becomes a rent-seeking opportunity for various stakeholders. The cure can sometimes be worse than the disease. Any training mandate requires built-in accountability measures and transparent, corruption-resistant implementation; otherwise, it risks becoming another tax on poor workers.

14. One in Four Battery Drivers Used to Pedal

About 24.5% of battery rickshaw drivers previously operated pedal rickshaws, representing the largest single occupational background among battery drivers. This reveals a clear migration pathway within the sector itself.

The remaining came from farming (21.35%), daily labor (5.21%), garment work (6.25%), and other informal occupations. The report explicitly states that “this potentially indicates that the battery rickshaw is attracting more workforce in the sector.”

Battery rickshaws are not just replacing pedal ones; they are expanding the sector entirely, pulling workers from across Bangladesh’s informal economy. This has significant implications: it is not a simple technology substitution, but sector expansion that is absorbing labor from agriculture and manufacturing.

This makes blanket bans particularly destructive. Such bans would not just affect existing rickshaw drivers; they would eliminate economic opportunities for rural migrants and displaced workers who view battery rickshaws as their best available option. To meaningfully address this challenge, stakeholders must create alternative economic opportunities to absorb these individuals.

15. The Capital Investment Gap is Enormous

According to the report, “92.50% pedal rickshaws cost between BDT 3,000–15,000, while 97.01% battery rickshaws are typically priced between BDT 35,000–200,000.”

This capital barrier fundamentally shapes ownership patterns. While 35% of pedal drivers own their vehicles (often purchased with personal savings), only 21% of battery drivers can claim ownership. The rest rent, paying daily fees that are three times higher than pedal equivalents. The report also suggests that battery rickshaw ownership pushes owners to rely on MFI and other forms of loans.

This ownership structure is deeply concerning. When the vast majority of operators do not own their means of production, they have minimal voice in how regulation affects them. Garage owners, who possess the capital and connections, will navigate any new regulatory framework. Drivers will bear the costs.

16. Microfinance Fuels the Battery Revolution (and Creates New Vulnerabilities)

The report found that “pedal rickshaws are primarily purchased using personal savings (60%), whereas battery rickshaws are more commonly financed through loans from NGOs or microfinance institutions (59.7%).”

The debt burden is substantial: “80% of battery rickshaw drivers borrow between BDT 40,000 and 120,000, with an average loan size of approximately BDT 80,000.”

This creates both opportunity and vulnerability. Drivers gain access to higher-earning vehicles but carry significant financial risk in an unregulated sector. One regulatory crackdown or police harassment campaign could prevent these drivers from making loan payments.

The reliance on microfinance suggests that any aggressive regulatory intervention should be carefully considered. These are not speculative investments; they are survival debts. Policy changes that disrupt earning potential could trigger a wave of defaults, harming both drivers and the microfinance institutions that serve low-income communities.

17. The Income Story Reveals Who Really Benefits

Here is where economics becomes interesting. The report provides detailed income breakdowns that reveal the sector’s actual power dynamics.

For rented vehicles, “the daily net income for rented pedal rickshaws is BDT 484, which is higher than the daily net income for rented battery rickshaws—BDT 418.” The higher rental costs eat into battery drivers’ earnings.

But for owners, the gap is dramatic: “a battery rickshaw generates a significantly higher income of BDT 970 daily” compared to BDT 530 for pedal rickshaws, nearly double.

The real beneficiaries appear to be garage owners who collect rent. The report calculates that “each rented battery rickshaw generates a gross revenue of BDT 832 per day, composed of the driver’s net income: BDT 418 and the weighted average of the rental payment to the owner: BDT 414.”

Consider that nearly half the gross revenue goes to the owner. The report itself notes this concern: “Possible exploitation of the battery rickshaw drivers may also be occurring, as almost half of the gross income is taken away from battery rickshaw drivers.”

This raises skepticism regarding regulations that primarily target drivers rather than ownership structures. The current system already extracts significant value from workers. Additional compliance costs will likely be passed down to drivers, not absorbed by owners.

18. The Real Challenge is Regulatory Capacity, Not the Rickshaws

Upon reviewing the data, a fundamental conclusion emerges: the challenge is not a lack of sound policy ideas; the Innovision report offers a thoughtful, multi-stakeholder framework that balances safety, livelihoods, and mobility needs.

The problem is that Bangladesh’s administrative state has repeatedly proven incapable of implementing nuanced regulations without turning them into harassment and rent-seeking opportunities.

Attempts have been made to formalize street vendors, small manufacturers, home-based workers, and various informal transport sectors. The result is usually: some formalization at the top end (those with capital and connections), continued informality in the middle, and intensified harassment at the bottom (those who cannot afford compliance or cannot navigate bureaucracy).

What Should Actually Be Done?

Considering these insights, several principles could guide future actions:

- Start with infrastructure, not enforcement. Build charging stations, create designated parking, and improve road surfaces in rickshaw-heavy areas. Provide services that make formalization attractive before demanding compliance.

- Keep rules simple and verifiable. “The vehicle has lights, brakes, and horn” can be checked in 30 seconds. “Vehicle meets BRTA Standard Specification 47B subsection 12” requires an expert and creates discretion. Minimize discretion.

- Create benefits for compliance. Registered rickshaws get charging access. Licensed drivers get accident insurance. Compliant garages get MFI credit. Make formality more profitable than informality, not just more legal.

- Pilot before scaling. Try zone-based regulations in one neighborhood, learn what actually works, adjust, then expand. Do not impose citywide systems that have never been tested.

- Build from existing structures. Garage owners already organize drivers, manage fleets, and maintain vehicles. Work through them rather than trying to reach hundreds of thousands of individuals. Create garage owner associations with formal status, then regulate those.

- Accept imperfect compliance. Aiming for 95% registration is futile and will create massive enforcement costs. Aiming for 60% might be achievable and still transform the sector’s safety and visibility.

- Ruthlessly punish official corruption. If poor drivers are asked to comply with rules, officials and stakeholders must be held to even higher standards. Any bribe-taking in rickshaw registration or enforcement should mean immediate termination, not just a warning. This matters more than the rules themselves.

- Monitor outcomes, not just inputs. Do not measure success by registrations issued or drivers trained. Measure accident rates, driver income stability, passenger satisfaction, and congestion impacts. If regulations are not improving these outcomes, change the regulations.

Endnote

The Innovision report documents a remarkable market-driven transformation. Without government planning, hundreds of thousands of workers have shifted toward battery rickshaws in response to real economic and physical incentives. Millions of passengers have voted with their daily choices, revealing preferences for speed despite safety concerns.

This represents the market at work: aggregating dispersed information, responding to incentives, and solving coordination problems that planners could not anticipate.

However, markets alone cannot solve collective action problems like safety externalities, congestion, and environmental impacts. That is the purpose of regulation.

The challenge lies in implementing regulations that genuinely help rather than merely imposing costs. Given Bangladesh’s administrative capacity and governance culture, this is not a technical problem; it is a political economy problem.

The Innovision report offers valuable evidence and a robust framework. However, the report, like any other, cannot provide the state capacity and political will necessary to implement nuanced regulation without corruption.

Until that fundamental challenge is addressed, imperfect markets with minimal regulation may be preferable to perfect regulations with corrupt implementation. Battery rickshaws could continue evolving through market forces, with infrastructure support provided where possible, and regulatory energy focused on the most critical safety interventions that are simple enough to be corruption-resistant.

That may not be the ideal outcome. But in Bangladesh’s current governance reality, it might be the best achievable one. And achieving modest improvements for millions of people is better than designing perfect systems that fail in practice.

The urban mobility transition is happening whether it is planned or not. The question is whether institutions can adapt to help, or whether they will simply impede progress.